Balancing Survival and Stability: The Dual Impact of Government Aid on Post-Relocation Income Recovery for Street Vendors

Abstract:

Across cities in the Global South, the relocation of informal street vendors has emerged as a dominant urban policy tool in the context of rapid urbanization, often justified through narratives of modernization and spatial order. Yet, such interventions have systematically displaced informal vendors from key commercial spaces, disrupting their livelihoods and social networks. This study interrogates these dynamics through a case study of Padang, Indonesia, where street vendors were relocated from a vibrant beach corridor to a designated commercial zone. Drawing on panel data and a survival analysis framework, the study investigates the temporal dimensions of income recovery post-relocation, with a focus on how differentiated forms of government assistance—mobile carts versus fixed stalls—shape recovery trajectories. The findings are contextualized within two theoretical frameworks. First, Amartya Sen’s capabilities approach. It emphasizes substantive freedoms beyond income restoration. Second, the political economy of informality. It frames informal vendors as actors embedded in contested governance systems. The study reveals that relocation, when implemented without sensitivity to vendor agency and spatial dynamics, can exacerbate exclusion and prolong economic vulnerability. By combining empirical rigor with normative inquiry, the research offers new insights into justice-oriented urban development in secondary cities of the Global South. It contributes to debates on informal urbanism by highlighting the importance of temporality, differentiated support mechanisms, and spatial inclusion in shaping recovery outcomes. Ultimately, the study challenges conventional relocation strategies and advocates for more adaptive, participatory, and capability-enhancing policy models.

1. Introduction

Across cities in the Global South, the relocation of informal street vendors has emerged as a dominant urban policy response to rapid urbanization and infrastructure-driven redevelopment. Justified under banners of modernization, spatial order, and economic revitalization, these interventions have systematically displaced informal workers from strategic public spaces, often with severe socio-economic consequences. In Latin America, for instance, Martínez & Young (2022) documented a rise in post-pandemic forced relocations in cities like Cali, Colombia, which fundamentally disrupted livelihoods and altered urban socio-spatial dynamics.

Similarly, across African cities, Adama (2020) chronicled “urban cleansing” strategies that prioritize aesthetics and commercial interests at the expense of the urban poor. In Southeast Asia, redevelopment frequently centers on tourism and city-branding, where schemes often privilege visitor comfort and a curated urban image over vendor survival. This exclusionary logic reflects a persistent planning tradition that frames informality as a barrier to modernity (Kamalipour & Dovey, 2020; Peimani & Kamalipour, 2022), reinforcing economic disenfranchisement and precarity among those who rely on the informal economy for their subsistence (Roever & Skinner, 2016).

While the detrimental outcomes of relocation—such as severed customer access, disrupted social networks, and significant income decline—are well-documented in cities from Lagos to Accra (Adama, 2021; Cobbinah, 2023), a critical dimension remains underexplored: the temporality of recovery. Existing studies, often relying on cross-sectional data or qualitative snapshots, provide valuable insights into vendor welfare before and after relocation, but they seldom answer the crucial questions of when and how quickly vendors recover. They fail to model the time-to-event of income restoration or investigate whether the pace of recovery varies systematically based on the form of government intervention or vendor characteristics.

Understanding this temporal trajectory is essential for designing policies that not only aim for recovery but also seek to minimize the duration of economic hardship and vulnerability. This study identifies the lack of a dynamic, time-sensitive analysis of post-relocation recovery as its central point of departure. In Indonesia, these tensions are particularly acute. Urban redevelopment, often driven by tourism and city-branding agendas, regularly clashes with a vast and diverse informal economy that employs a significant portion of the urban population. The city of Padang presents a critical and compelling case study. Here, street vendors were relocated from the vibrant Purus Beach corridor to the designated Lapau Panjang Cimpago zone as part of a broader urban modernization drive, mirroring interventions seen in larger cities like Jakarta (Aristyowati et al., 2024) and raising important questions about governance and spatial justice (Rahayu et al., 2025).

Unlike the uniform relocation strategies documented elsewhere, the Padang case introduced a natural experiment through a differentiated assistance scheme: some vendors received mobile carts, while others were allocated semi-permanent stalls. This policy variation creates a unique opportunity for a comparative analysis of how different forms of capital assistance—emphasizing mobility versus fixedness—shape economic recovery trajectories. Furthermore, as a mid-sized secondary city, Padang remains understudied in the urban informality literature, offering fresh insights beyond the typical megacity focus.

This study is guided by the integration of two powerful theoretical frameworks to provide a multidimensional analysis of recovery. First, Amartya Sen’s capabilities approach (Sen, 1999) shifts the evaluative focus beyond mere income restoration to the expansion of substantive freedoms—what people are able to be and do. In the context of relocation, a successful recovery thus entails regaining the freedom to choose one’s livelihood, to be economically mobile, and to live with dignity. A policy that restores income but confines a vendor to an unprofitable, fixed location would be a failure in capability terms.

Second, the political economy of informality frames street vendors not as marginal actors but as agents embedded within contested governance systems where state interventions reflect deeper political priorities and notions of urban order (Kamalipour & Dovey, 2020; Martínez & Young, 2022). This lens helps us understand relocation not as a neutral technical exercise, but as an ideological act that shapes who belongs in the city and under what terms. By combining these frameworks, we analyze relocation not merely as a spatial or economic shock, but as a process that either constrains or enhances vendors’ capabilities, a process fundamentally shaped by the political logic of urban governance.

Employing a survival analysis framework on longitudinal panel data, this study investigates the post-relocation income recovery of street vendors in Padang. It is driven by three research questions: How do differentiated forms of government assistance (mobile carts vs. fixed stalls) influence the pace and sustainability of income recovery? What role do individual vendor characteristics, such as initial capital, gender, and business experience, play in shaping recovery trajectories? And how do institutional and spatial contexts mediate the process of post-displacement recovery? In answering these, the study makes three primary contributions.

Empirically, it offers one of the first longitudinal, quantitative analyses of post-relocation income recovery among street vendors in a secondary Indonesian city, providing novel evidence on how policy design shapes economic trajectories. Methodologically, it demonstrates the utility of survival analysis—a technique common in biostatistics—for modeling time-to-event data in urban livelihood studies, offering a robust alternative to static regression models. Theoretically, it advances the literature on urban informality by integrating Sen’s normative capabilities framework with a structural political economy perspective, using empirical data to show how post-displacement recovery is a temporally extended process of renegotiating one’s freedom and position within the city.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. The next chapter reviews the literature on urban redevelopment, displacement, and vendor recovery. This is followed by an outline of the survival analysis methodology, a presentation of the results, and a discussion of these findings in relation to the theoretical frameworks. The paper concludes with the study’s implications for justice-oriented urban policy in the Global South.

2. Literature Review

This chapter situates the study within the broader scholarly discourse on urban informality, displacement, and livelihood recovery. The existing literature provides crucial insights into the complex dynamics of street vending in the Global South, particularly in the context of urban redevelopment and governance. However, significant gaps remain in understanding the temporal dimensions of economic recovery following forced relocation.

This review synthesizes key theoretical and empirical contributions across four thematic areas: the governance of urban informality in redevelopment contexts, the multifaceted impacts of displacement, the processes and determinants of vendor recovery, and the theoretical frameworks that inform our understanding of these phenomena. By critically examining these bodies of literature, this chapter establishes the conceptual foundation for investigating the temporal dynamics of income recovery among relocated street vendors in Padang, Indonesia, while clearly identifying the research gaps that this study aims to address.

Urban redevelopment in the Global South has increasingly been driven by a pursuit of spatial order, aesthetic enhancement, and investment attraction. Kamalipour & Dovey (2020) argue that contemporary urban transformation projects often frame informal economic activities as disruptors to the modern urban image, leading to their systematic removal from strategic public spaces. This “aestheticization of urban space” frequently privileges tourism and middle-class consumption over the livelihood needs of the urban poor.

The governance of street vending reflects what Martínez & Young (2022) term “spatial purification”—planning practices that seek to eliminate visual markers of poverty from central urban areas. In this context, informal vendors are often constructed as obstacles to modernity rather than as legitimate economic actors (Peimani & Kamalipour, 2022). This framing has profound implications for urban policy, as it justifies exclusionary practices under the guise of urban improvement and order.

However, this dominant framing has been robustly critiqued by scholars who emphasize the embeddedness and rationality of informal systems. As Cobbinah (2023) demonstrates, informal vending is not merely opportunistic but is rooted in longstanding socio-economic networks, cultural practices, and spatial routines that constitute the very fabric of many Southern cities. The failure to acknowledge these embedded logics often results in exclusionary and unsustainable policies that undermine urban vitality and economic diversity.

The displacement resulting from urban redevelopment generates cascading effects that extend far beyond spatial relocation. Adama (2021) documents how forced evictions in African cities disrupt not only vendors’ spatial positioning but also the social networks and economic relationships that underpin their livelihoods. This “social-spatial disruption” creates what Cobbinah (2023) identifies as a double precarity—the loss of both economic security and social protection systems.

Studies across multiple contexts reveal consistent patterns of post-relocation hardship. In Latin America, Martínez & Young (2022) found that relocated vendors faced reduced customer access, inadequate infrastructure, and regulatory ambiguity in their new locations. Similarly, research in Southeast Asia shows that beautification projects often relocate vendors to peripheral sites with minimal foot traffic, leading to dramatic income declines (Peimani & Kamalipour, 2022). These findings underscore what Kamalipour & Peimani (2021) term the “infrastructure mismatch”—the disconnect between the physical provisions in relocation sites and the actual operational needs of vendors.

The consequences extend beyond immediate economic losses. As Adama (2021) observes in Nigerian cities, displacement weakens collective vendor networks and their capacity for collective action, leading to increased individualization of risk and vulnerability. This erosion of social capital represents a critical but often overlooked dimension of displacement impacts.

The literature on vendor adaptation and recovery reveals complex and uneven patterns. While some vendors demonstrate remarkable resilience, recovery is often contingent on a combination of structural and individual factors. Anja & Zhang (2023) highlight the crucial role of social capital and household survival strategies in post-displacement resilience in Ethiopian cities. Their research shows that vendors with strong social networks are better positioned to navigate the challenges of relocation.

Spatial factors emerge as particularly significant in shaping recovery trajectories. Rahayu et al. (2025) demonstrate that spatial flexibility—particularly the ability to maintain mobility through tools like carts—facilitates quicker recovery compared to static vending arrangements. This finding aligns with Peimani & Kamalipour (2022) emphasis on “spatial agency”—the capacity of vendors to actively shape their operational environments rather than being confined to predetermined spaces.

The literature also identifies several key individual and demographic factors that mediate recovery. Kamalipour (2022) notes that women vendors, who often juggle caregiving and economic responsibilities, face additional constraints in adapting to new vending environments. Similarly, initial capital endowment, prior business experience, and access to informal credit emerge as important resources that can mitigate post-relocation hardship (Cobbinah, 2023; Martínez & Young, 2022).

However, a significant limitation persists in this literature: the predominance of static, cross-sectional analyses that provide snapshots of recovery rather than modeling its temporal dynamics. While we know that recovery occurs, we understand remarkably little about when it happens, how quickly it unfolds, and whether the pace varies systematically across different groups or policy interventions.

This study draws on two complementary theoretical frameworks to address these gaps. First, Amartya Sen's capabilities approach (1999) provides a normative foundation for evaluating recovery beyond income metrics. This framework emphasizes substantive freedoms—the real opportunities people have to lead the lives they value. In the context of vendor relocation, recovery thus entails not just income restoration but the regeneration of capabilities such as spatial mobility, economic choice, and social participation (Cobbinah, 2023).

The political economy of informality complements this normative focus by situating street vendors within broader structures of urban governance and power. This perspective, advanced by scholars like Kamalipour & Dovey (2020) and Martínez & Young (2022), frames informality not as a separate sector but as produced through specific regulatory regimes and governance arrangements. From this vantage point, relocation policies reflect not technical solutions but political choices about whose interests and visions of the city should prevail.

Together, these frameworks enable a multidimensional analysis of recovery that attends to both individual experiences and structural constraints. They allow us to examine how relocation policies expand or constrain vendors’ capabilities within specific political-economic contexts marked by contested notions of urban order and legitimacy.

This review identifies three critical gaps in the existing literature. First, there is a pronounced methodological gap in understanding the temporality of recovery—how it unfolds over time rather than at discrete points. Second, while the importance of policy design is widely acknowledged, we lack systematic comparisons of how different forms of assistance shape recovery trajectories. Third, the integration of normative frameworks (like capabilities) with empirical analysis of recovery processes remains underdeveloped, particularly in secondary cities of the Global South.

This study addresses these gaps through a longitudinal analysis of vendor recovery in Padang, Indonesia. By examining a natural experiment involving different assistance types (carts vs. stalls), it provides unique insights into how policy instruments shape recovery dynamics. Methodologically, it introduces survival analysis to the study of urban livelihoods, enabling precise modeling of recovery timing. Theoretically, it bridges normative and structural perspectives to develop a more comprehensive understanding of what constitutes successful recovery and how it might be achieved.

The Padang case is particularly instructive as a mid-sized secondary city where patterns of urban governance and informality may differ from the megacities that dominate the literature. By focusing on this understudied context, the study contributes to a more geographically nuanced understanding of urban informality and displacement in the Global South.

3. Methodology

This chapter outlines the research methodology employed to investigate the temporal dynamics of income recovery among relocated street vendors in Padang, Indonesia. The study adopts a quantitative longitudinal approach, utilizing survival analysis to examine how different forms of government assistance and individual characteristics influence the time to income recovery following forced relocation. This methodological approach addresses critical gaps in the existing literature by capturing the dynamic nature of recovery processes rather than relying on static snapshots.

The chapter begins by justifying the selection of survival analysis as an appropriate methodological framework, followed by detailed descriptions of data collection procedures, variable operationalization, and analytical techniques. Special attention is given to methodological rigor through comprehensive diagnostic testing and robustness checks, ensuring the reliability and validity of findings for policy recommendations in urban informality contexts.

Economic recovery following disruptive events like forced relocation represents a complex process characterized by inherent uncertainty and multiple influencing factors. As noted by Ali et al. (2021) and Kamalipour & Peimani (2021), effective recovery requires the integration of various elements, including appropriate public assistance and broader economic strategies. In the context of street vendor relocation in Padang City, this disruption has exerted significant pressure on economic stability, manifesting as reduced revenues, customer loss, diminished business opportunities, and substantial government expenditure (Cobbinah, 2023; Martínez & Young, 2022). Addressing these challenges promptly is crucial for restoring economic stability, necessitating methodological approaches that can accurately model recovery timing and determinants.

This study employs survival analysis as its primary analytical framework, specifically suited for examining time-to-event data where the event of interest is income recovery. Traditional regression techniques, including Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) and logistic/probit regression, prove inadequate for several reasons. First, OLS fails to account for censoring—cases where recovery had not occurred by the study’s conclusion—leading to biased and inconsistent estimates. Second, while probit and logistic models handle binary outcomes, they ignore the crucial temporal dimension and cannot evaluate recovery pace or timing (Hosmer & May, 2008). Survival analysis overcomes these limitations by explicitly incorporating time-to-event data and properly handling right-censored cases, making it ideal for analyzing longitudinal economic trajectories where the event of interest may or may not occur during the observation period.

The research population comprises all 103 street vendors relocated from Pantai Purus to Lapau Panjang Cimpago between January and March 2023. By employing a census design that includes the entire population, the study avoids sampling bias and enhances internal validity (Babbie, 2020). Data collection utilized structured interviews conducted in three waves over twelve months, supplemented by administrative relocation records from the Padang City Trade Office. The study adhered to strict ethical standards, with participants fully informed of the research purpose and providing written consent. All data were anonymized and securely stored in accordance with research ethics principles (Bryman, 2016).

The dependent variable, time to income recovery, measures the number of months required for vendors to return to pre-relocation income levels. This operationalization acknowledges the practical limitation that recalling real income adjusted for inflation was deemed unreliable for this population. While nominal income measurement presents limitations, it represents the most immediate and tangible benchmark for vendors themselves in assessing economic recovery. Right-censoring is applied for cases where recovery had not occurred by the study’s conclusion.

The key independent variable, type of government assistance, is dichotomized into two categories: mobile carts (coded 0) and borrowed vending spaces (coded 1). This dichotomization reflects fundamentally different state interventions—one emphasizing flexibility and mobility, the other spatial fixity and formality (Peimani & Kamalipour, 2022). The binary coding simplifies model interpretation through hazard ratios (HRs) while aligning with observable policy categories in the field. Table 1 presents comprehensive descriptive statistics for all variables, providing a foundation for subsequent multivariate analysis.

Variable | Description | Obs | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

Initial capital (In_cap) | This variable captures the initial capital of street vendors across three distinct groups. Group 0: 60,000–250,000; Group 1: 251,000–500,000; Group 2: 501,000–2,500,000. | 103 | 1.1456 | 0.6775 | 0 | 2 |

Help from government (gov) | This variable captures whether the street vendor received government assistance. Group 1: Borrowed place; Group 0: Received a cart. | 103 | 0.3592 | 0.4821 | 0 | 1 |

Help from family (family) | This variable measures the level of support from family members, ranging from emotional to financial assistance. | 103 | 0.6117 | 0.8771 | 0 | 2 |

Control variables | ||||||

Gender | Accounts for potential gender differences in economic recovery. 0: Female; 1: Male. | 103 | 0.6796 | 0.4689 | 0 | 1 |

Age | Considers the age of the street vendors, with varying levels of resilience and adaptability across different age groups. | 103 | 41 | 10.001 | 24 | 66 |

Length of business experience (Lob) | Captures the street vendors’ experience in selling, which may impact their economic recovery. 1: Less experience; 2: More experience. | 103 | 1.3398 | 0.4760 | 1 | 2 |

Time | Represents the time (in months) until income recovery. | 103 | 42.8641 | 13.0542 | 24 | 53 |

Censor | Indicates whether the data is censored (i.e., whether the event of interest has occurred or not). 0: Not censored; 1: Censored. | 103 | 0.6796 | 0.4689 | 0 | 1 |

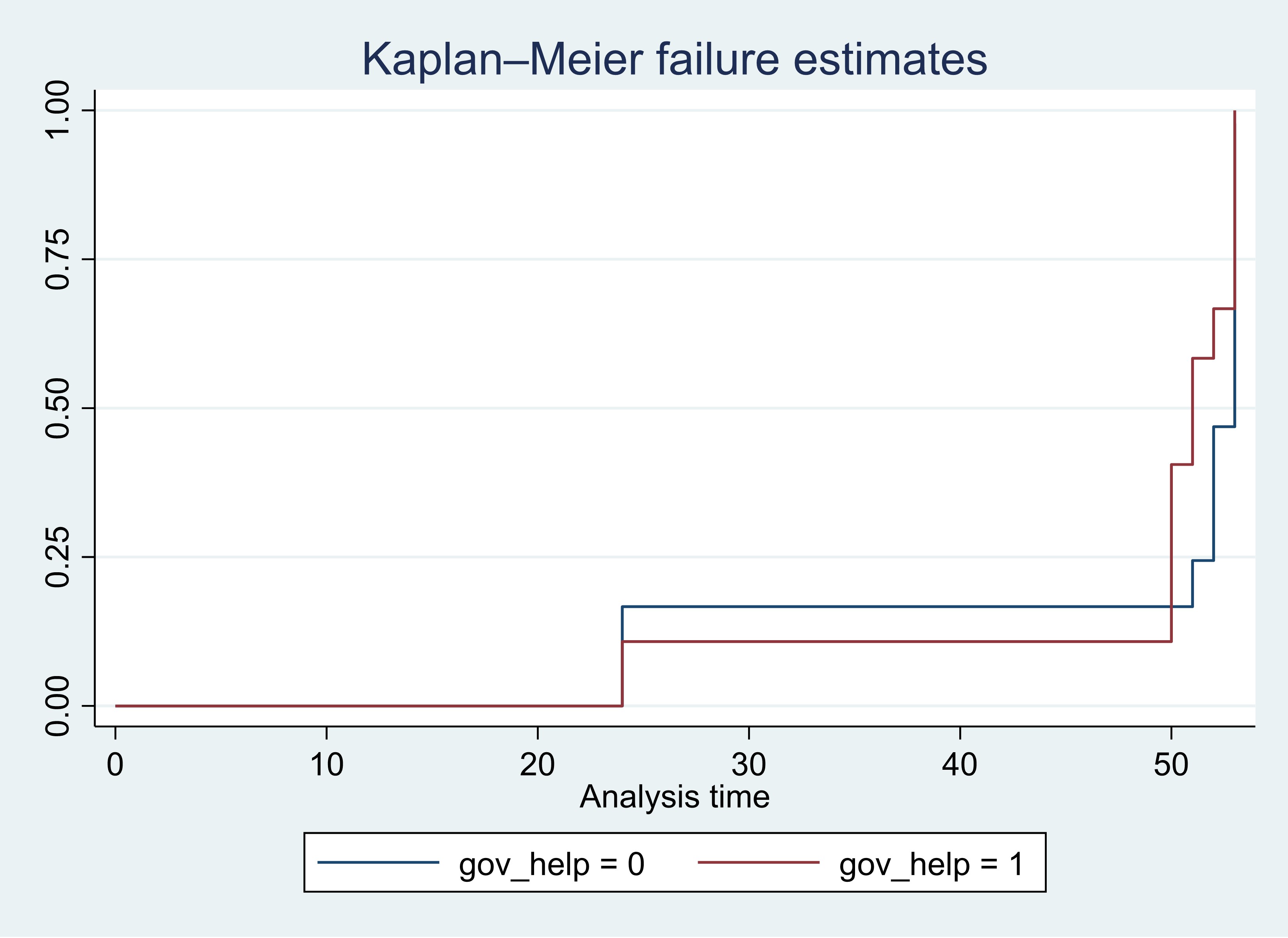

The analysis begins with non-parametric Kaplan-Meier estimation to visualize and compare survival probabilities—representing the probability of not having recovered income—across different vendor groups. Specifically, Kaplan-Meier curves distinguish between vendors receiving different forms of government assistance, providing initial insights into relative recovery speeds and stability. The log-rank test assesses statistical significance between groups, serving as precursor to multivariate modeling by highlighting disparities in recovery trajectories (Cleves et al., 2008).

To control for confounding variables and estimate covariate effects on recovery likelihood, the Cox Proportional Hazards model is implemented. The model takes the form:

where, h(t) represents the hazard function at time t given covariates X, h₀(t) is the baseline hazard function, and βₖ are estimated coefficients interpreted as log HR. HR greater than 1 indicate faster recovery, while ratios less than 1 suggest slower recovery. Model diagnostics include Likelihood Ratio, Wald, and Score tests to confirm overall model fit and covariate significance (Hosmer & May, 2008; Cleves et al., 2008).

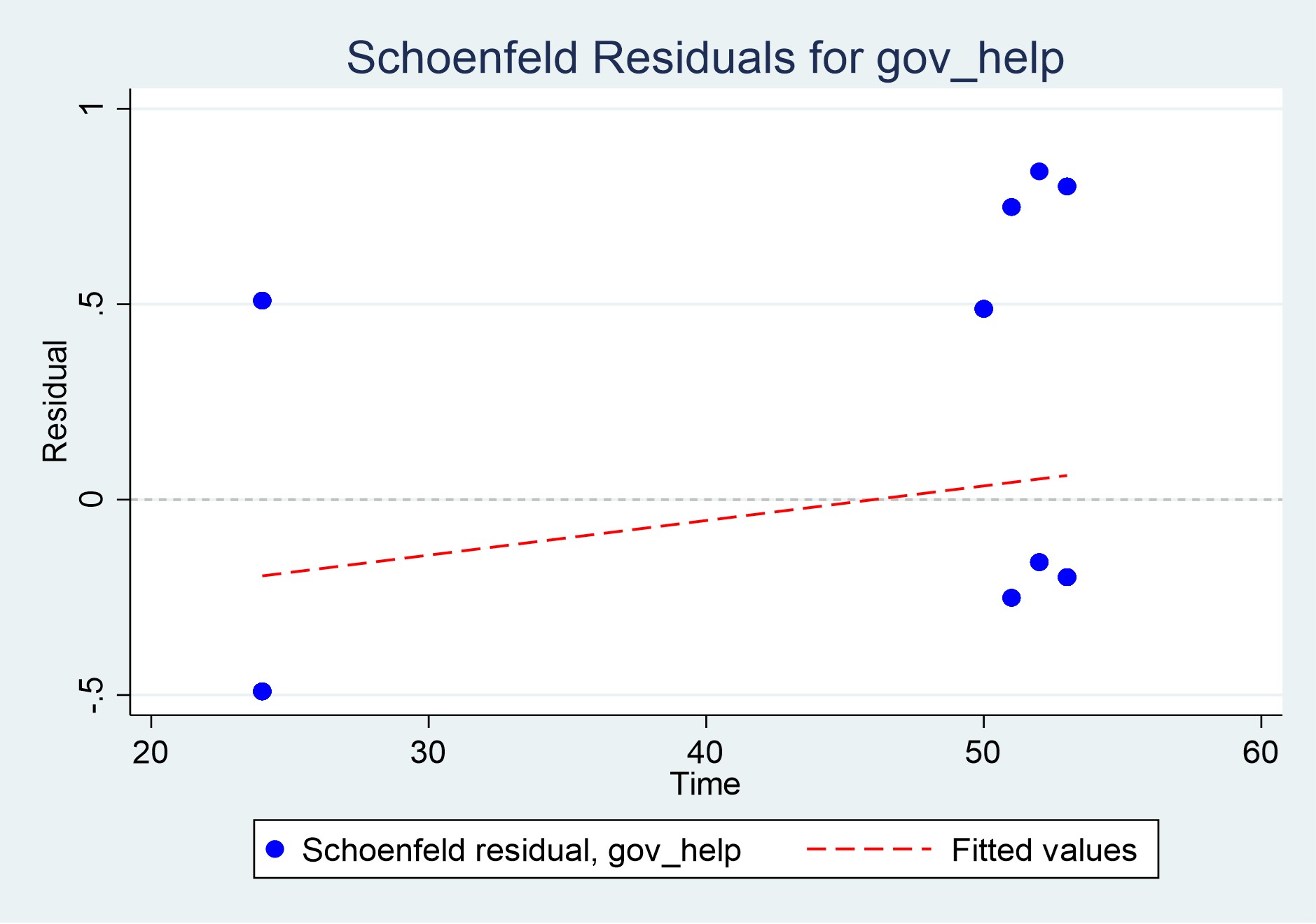

The Cox model’s validity hinges on the proportional hazards (PH) assumption, requiring constant HR over time (Allison, 2014). Verification employs both statistical and graphical diagnostics. Schoenfeld residuals are computed and examined for each covariate, plotted against time to detect systematic patterns. The global test for proportionality (estat phtest) indicates whether the assumption holds across covariates (Grambsch & Therneau, 1994). Complementary log-minus-log survival plots assess curve parallelism among groups, with non-intersecting curves supporting PH assumption validity ( Cleves et al., 2008).

To ensure reliable and valid findings, the study implements multiple diagnostic tests and robustness checks assessing statistical soundness, predictive discrimination, and sensitivity to alternative specifications. Multicollinearity among independent variables is examined using Variance Inflation Factor (VIF), with values below 2 indicating no problematic collinearity that could distort coefficient estimates (Gujarati & Porter, 2009). The model’s discriminatory capacity is evaluated using Harrell’s concordance statistic (C-index), with values above 0.6 indicating acceptable predictive accuracy.

Sensitivity analysis includes re-estimating the Cox model on subsamples excluding censored observations and introducing interaction terms, particularly between government assistance and initial capital. Although interaction terms may not achieve statistical significance, stability in core predictor direction and magnitude across specifications indicates robust findings (Allison, 2014).

Finally, non-parametric bootstrap procedures with 1,000 replications test the robustness of standard errors and confidence intervals. This approach confirms significance and stability of primary predictors, demonstrating model resilience to resampling variation. Collectively, these procedures provide strong support for statistical reliability, internal consistency, and interpretability of the Cox proportional hazards estimates.

The research design incorporates several ethical considerations, including informed consent, confidentiality protection, and data anonymization. Methodologically, the study acknowledges limitations in using nominal income measures and potential recall bias in self-reported data. However, the comprehensive analytical framework, combining multiple estimation techniques and robustness checks, mitigates these concerns while providing novel insights into the temporal dynamics of post-relocation recovery. This methodological approach not only addresses the research questions but also contributes to methodological innovation in urban informality studies by demonstrating the utility of survival analysis for understanding dynamic livelihood trajectories in contested urban spaces.

4. Results and Analysis

This chapter presents the empirical findings from the survival analysis examining the temporal dynamics of income recovery among relocated street vendors in Padang. The analysis progresses systematically from descriptive explorations to multivariate modeling, providing a comprehensive understanding of how different factors influence recovery trajectories. Beginning with non-parametric Kaplan-Meier estimates, we visualize recovery patterns across key subgroups, followed by Cox proportional hazards regression to identify significant determinants of recovery speed. The chapter further validates methodological assumptions through rigorous diagnostic testing and concludes with robustness checks to ensure the reliability of our findings. This structured approach enables us to address our core research questions while maintaining statistical rigor, ultimately revealing how policy interventions and individual characteristics shape the pace of economic recovery in post-relocation contexts.

The initial analysis employs Kaplan-Meier survival curves to visualize income recovery patterns across vendors receiving different forms of government assistance. Figure 1 presents distinct recovery trajectories between Group 0 (vendors receiving mobile carts, blue line) and Group 1 (vendors allocated borrowed stalls, red line). The survival curves, representing the probability of not having achieved income recovery, reveal significant disparities in recovery speed between the two groups.

Vendors receiving mobile carts (Group 0) demonstrate a steeper decline in their survival curve, indicating faster income recovery. The early dip in the curve suggests that a substantial proportion of cart recipients achieved income restoration within the first few months post-relocation. This pattern aligns with the operational flexibility afforded by mobile carts, enabling vendors to quickly adapt to new market conditions and seek out customers in various locations (Hernandez, 2023).

Conversely, vendors allocated fixed stalls (Group 1) exhibit a more gradual recovery trajectory, with their survival curve remaining elevated for a longer duration. This pattern reflects the challenges associated with establishing stationary businesses in new locations, including the time required to build customer bases and adapt to different market dynamics (Brown et al., 2010). The log-rank test confirms the statistical significance of these differences ($X²$ = 8.34, p = 0.004), validating the visual observation that assistance type substantially influences recovery speed.

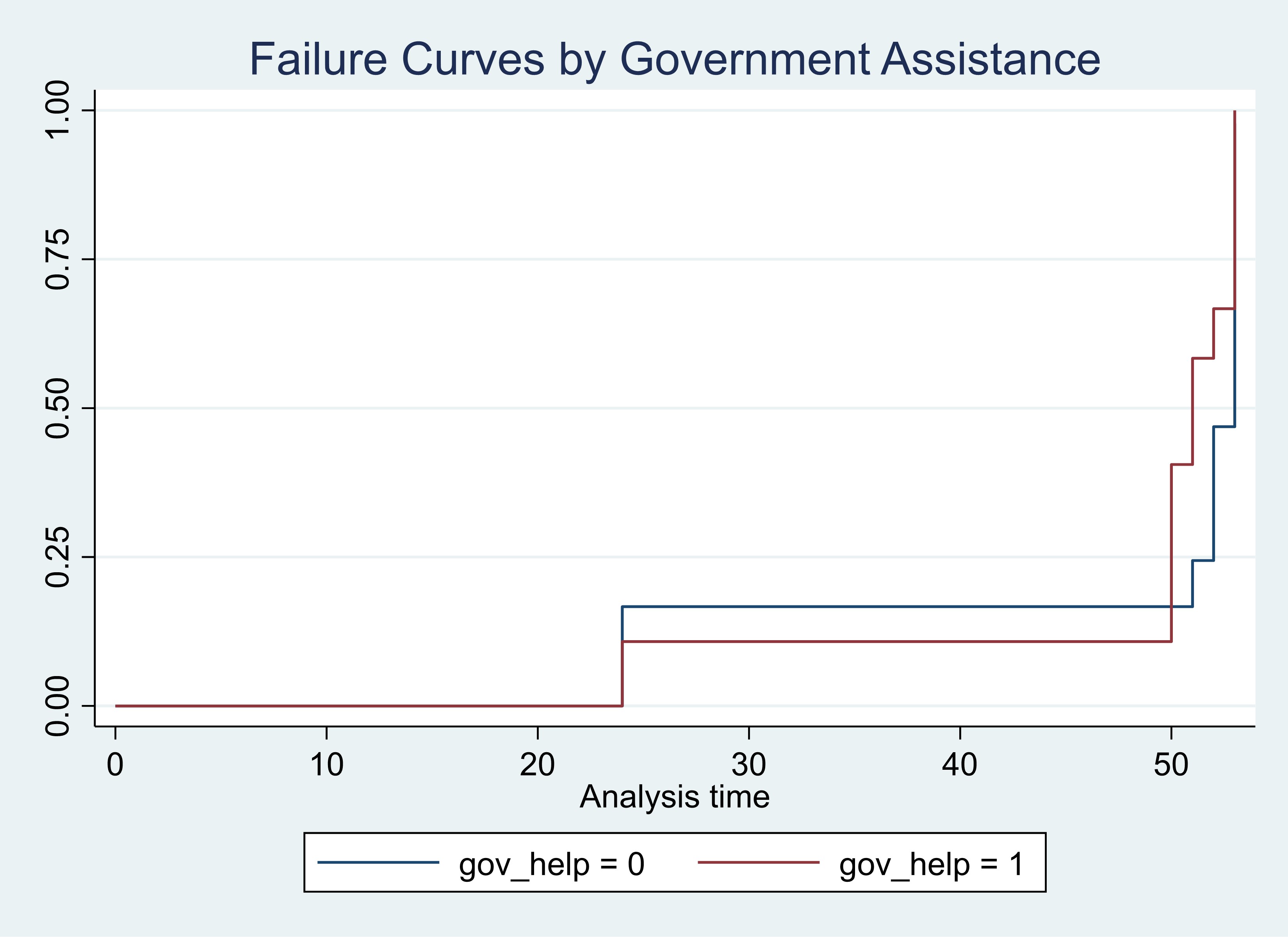

Figure 2 presents Kaplan-Meier curves stratified by initial capital levels, revealing another dimension of recovery heterogeneity. Vendors are categorized into three groups based on pre-relocation capital: Group 0 (IDR 60,000–250,000), Group 1 (IDR 251,000–500,000), and Group 2 (IDR 501,000–2,500,000). The analysis yields a counterintuitive yet statistically significant pattern (log-rank test: $X²$ = 6.28, p = 0.012).

Vendors with the lowest initial capital (Group 0) demonstrate the fastest recovery, as evidenced by their steep survival curve decline. This rapid recovery may be attributed to lower absolute income thresholds for recovery, greater experience with economic uncertainty, and reliance on informal survival strategies. In contrast, higher-capital vendors (Group 2) exhibit the slowest recovery, possibly due to more complex business operations, higher income recovery thresholds, and greater challenges in reestablishing customer networks suitable for their business scale.

The middle-capital group (Group 1) shows an intermediate recovery pattern, suggesting a non-linear relationship between initial resources and recovery speed. These findings challenge conventional assumptions that greater capital endowment automatically translates to faster recovery, highlighting instead the potential “liability of embeddedness” faced by previously successful vendors in new environments.

Building on the descriptive findings, we employ Cox proportional hazards regression to isolate the effects of various factors on recovery speed while controlling for potential confounders.

Variable | Description / Summary | HR | p-value | 95% CI |

Gender (Male = 1) | 52% male | 1.079 | 0.731 | 0.66–1.77 |

Age (years) | Mean = 41.7 (SD = 9.4) | 0.987 | 0.268 | 0.96–1.01 |

Vendor experience (years) | Mean = 8.2 (SD = 6.1) | 1.034 | 0.172 | 0.98–1.09 |

Family support (contributors) | Mean = 1.7 (SD = 0.9) | 1.142 | 0.201 | 0.92–1.41 |

Initial Capital–Low (ref.) | 33% | — | — | — |

Initial Capital–Medium | 41% | 0.823 | 0.548 | 0.44–1.55 |

Initial Capital–High | 26% | 0.359 | 0.012 | 0.16–0.81 |

Government assistance (Yes = 1) | 45% | 2.218 | 0.008 | 1.23–3.99 |

Type of stall (Fixed = 1) | 61% fixed | 0.612 | 0.047 | 0.38–0.99 |

Median recovery time (months) | 14.0 | — | — | — |

Model fit | LR χ² (9) = 27.64; Log-likelihood = -233.7 | — | p = 0.001 | — |

Table 2 presents the coefficient estimates across progressively specified models, with Table 3 (Table A2) providing the corresponding HR for interpretation. The multivariate analysis reveals several key patterns. Government assistance type emerges as a robust predictor of recovery speed across all model specifications. Vendors receiving mobile carts experience significantly faster recovery (HR = 2.14, p < 0.01 in the full model), with HR consistently above 2.0 indicating more than double the recovery speed compared to stall recipients. This finding substantiates the initial Kaplan-Meier results while controlling for other factors.

x2 | x4 | x7 | |

1.in_capital | -0.1388 | -0.1323 | -0.1252 |

-0.3 | -0.32 | -0.33 | |

2.in_capital | -0,8170** | -0,7982** | -0.7898* |

-0.38 | -0.4 | -0.41 | |

1.gov_help | 0.7223** | 0,7133** | 0.7629** |

-0.3 | -0.3 | -0.31 | |

age | 0.0026 | 0.0033 | |

-0.01 | -0.01 | ||

1.family_h~p | 0,1560 | 0.2285 | |

-0.42 | -0.44 | ||

2.family_h~p | 0.0305 | 0.0301 | |

-0.27 | -0.29 | ||

1.gender | -0.0512 | ||

-0.28 | |||

lob | -0.2457 | ||

-0.3 | |||

N | 103 | 103 | 103 |

Initial capital maintains its counterintuitive relationship with recovery speed in the multivariate context. Compared to the low-capital reference group, high-capital vendors show significantly slower recovery (HR = 0.45, p < 0.05), while middle-capital vendors display no statistically significant difference. This pattern persists across model specifications, suggesting that the disadvantage faced by higher-capital vendors is not attributable to other measured characteristics. Notably, demographic and social variables show limited explanatory power in the multivariate context. Age, gender, family support, and business experience all fail to achieve statistical significance across models. This suggests that in the context of profound structural disruption like forced relocation, institutional interventions and economic resources may overpower the influence of individual-level characteristics on recovery timing.

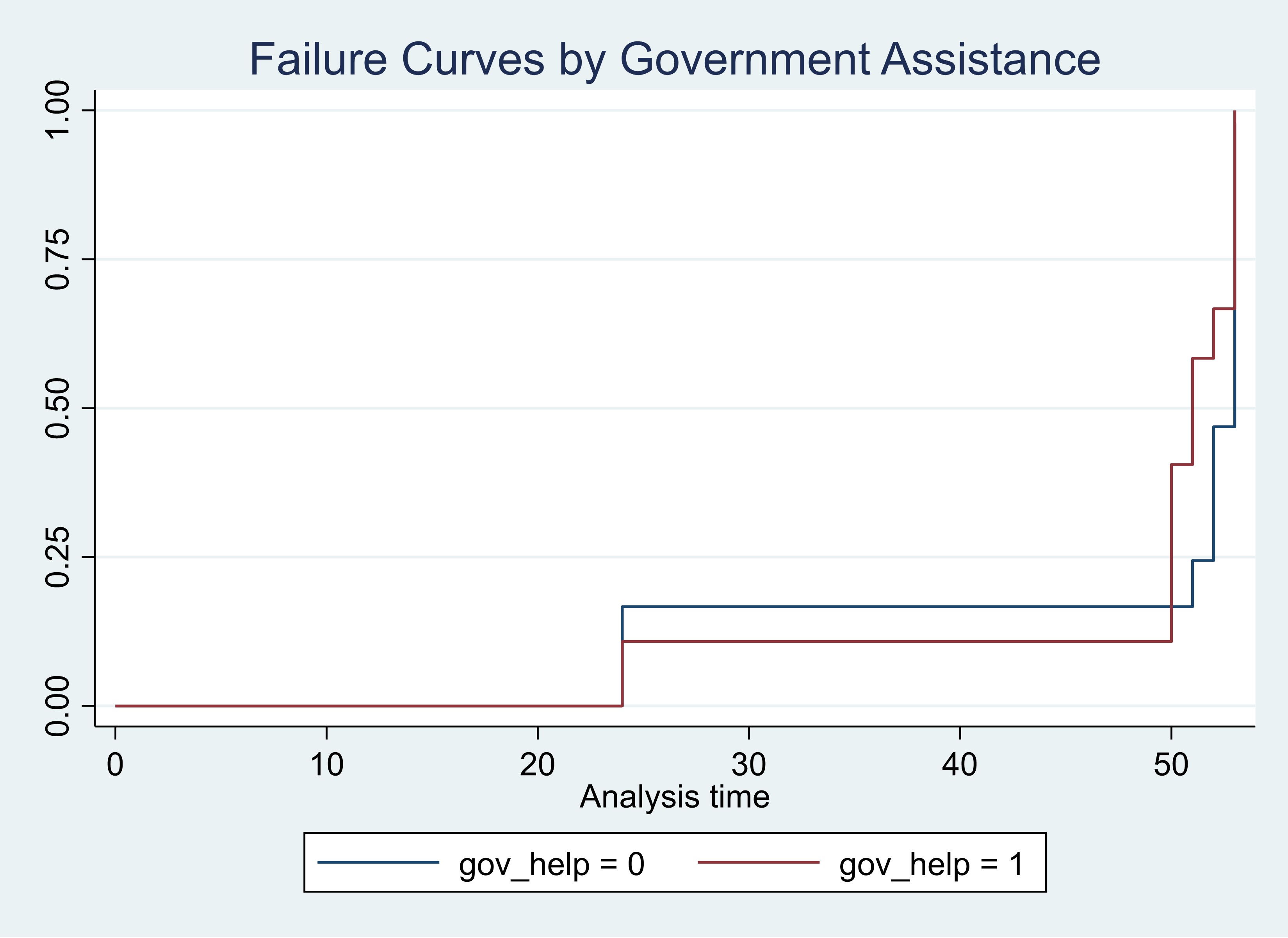

The validity of our Cox regression results depends on the proportional hazards assumption, which requires constant hazard ratios over time. We employ both graphical and statistical diagnostics to verify this critical assumption. Figure 3 presents log-minus-log survival plots for government assistance types, showing parallel curves that support the proportionality assumption.

Similarly, Figure 4 demonstrates generally parallel trajectories across capital groups, with minor deviations that do not substantially violate the assumption.

Statistical testing using Schoenfeld residuals (Table A3) provides complementary evidence. The global test for model proportionality yields a non-significant result ($X²$ = 9.34, p = 0.314), indicating no systematic violation of the PH assumption. Individual covariate tests show most variables comfortably meeting the proportionality requirement, with government assistance showing a marginal violation (p = 0.058) that does not reach conventional significance thresholds. The Schoenfeld residual plot for government assistance shows randomly distributed residuals around zero, further supporting the appropriateness of the Cox model. These comprehensive diagnostics provide confidence that the proportional hazards assumption is reasonably met, validating our interpretation of the HR.

We assess the model’s predictive accuracy using Harrell's concordance statistic, which yields a C-index of 0.645 (Appendix). This indicates moderate discriminative ability, with the model correctly ordering recovery times in approximately 65% of comparable vendor pairs. While this falls short of perfect prediction, it represents acceptable performance for social science applications and substantially outperforms random ordering (Somers’ D = 0.290).

To evaluate the sensitivity of our findings to censoring patterns, we conduct a subsample analysis using only vendors who experienced recovery during the study period (N = 70). Appendix compares results between the full sample and event-only subsample. Government assistance remains statistically significant in both specifications (HR = 2.03 in full sample vs. HR = 2.19 in event-only sample), demonstrating the robustness of this key finding. However, the effect of high initial capital diminishes in statistical significance when censored cases are excluded (HR = 0.43, p = 0.037 in full sample vs. HR = 0.62, p = 0.259 in event-only sample). This sensitivity highlights the importance of including censored observations to fully capture the delayed recovery experienced by some higher-capital vendors.

Non-parametric bootstrap analysis with 1,000 replications provides further validation of our core findings (Appendix). The bootstrap estimates closely mirror our primary results, with government assistance (HR = 2.03, 95% CI: 1.07–3.84) and high initial capital (HR = 0.43, 95% CI: 0.23–0.81) maintaining their statistical significance and effect magnitudes. The stability of these estimates across resampling procedures strengthens confidence in their reliability. The bootstrap results also confirm the non-significance of demographic and social variables, with all confidence intervals spanning unity. This consistency across estimation approaches reinforces our conclusion that institutional and economic factors dominate individual characteristics in determining recovery speed following relocation.

5. Discussion

This chapter synthesizes and interprets the key findings from our survival analysis of income recovery among relocated street vendors in Padang, contextualizing them within broader theoretical frameworks and existing literature. The empirical results reveal complex patterns that challenge conventional assumptions about post-displacement recovery and policy effectiveness. By integrating our findings with Amartya Sen’s capabilities approach and the political economy of informality, we develop a multidimensional understanding of how different forms of government assistance, varying levels of initial capital, and individual characteristics collectively shape recovery trajectories. This discussion moves beyond technical findings to explore their profound implications for urban justice, governance, and the substantive freedoms of informal workers in cities of the Global South.

Our most robust finding—the significantly faster recovery among vendors receiving mobile carts compared to those allocated fixed stalls—demands careful theoretical interpretation. Through Sen’ s capabilities lens, the cart transcends its material function as a vending tool to become an instrument that enhances spatial agency and operational flexibility. It restores the vendor's capability to seek out customers, adapt to daily fluctuations in foot traffic, and respond swiftly to new economic opportunities—fundamental freedoms that are often systematically stripped away by fixed-location relocations (Sen, 1999). This finding powerfully demonstrates that recovery encompasses more than income restoration; it involves regenerating the capacity to pursue one's livelihood with dignity and autonomy.

The political economy perspective further illuminates why different assistance forms yield divergent outcomes. The preference for fixed stalls often reflects what Kamalipour & Dovey (2020) identify as the state's desire for spatial order and legibility—a modernist planning imperative that values control and aesthetics over functional livelihood needs. Our results reveal that this imposed order comes at a significant short-to-medium-term economic cost to vendors, highlighting a fundamental tension between state control objectives and vendor livelihood security. The mobile cart, while perhaps less aligned with visions of “orderly” urban space, proves dramatically more effective at facilitating economic recovery, raising critical questions about whose interests ultimately shape urban policy.

The counterintuitive finding that vendors with higher initial capital experienced slower recovery challenges simplistic assumptions about the relationship between resources and resilience. This paradox can be understood through the concept of "embeddedness liability"—where pre-relocation success, often built on location-specific customer loyalty, specialized operations, and complex supply networks, becomes a disadvantage when those location-specific assets are destroyed (Martínez & Young, 2022). Higher-capital vendors likely lost not just income but also intangible, place-based capital that proves difficult to recreate in new environments.

Our sensitivity analysis further illuminates this dynamic. The fact that the capital effect weakened when censored observations were excluded suggests that the recovery challenges faced by better-off vendors are particularly pronounced among those with the longest recovery times. This underscores the methodological importance of accounting for right-censoring in survival analysis, as excluding these cases would have obscured an important dimension of the recovery experience. The finding complicates vulnerability assessments that equate higher income with lower need for post-relocation support, suggesting instead that previously successful vendors may require targeted assistance to rebuild the complex business ecosystems that underpinned their pre-relocation success.

The consistent statistical insignificance of demographic and social variables—including gender, age, family support, and business experience—presents another noteworthy finding. This pattern suggests that in the context of profound structural disruption like forced relocation, the effects of macro-level institutional interventions and economic resources may overpower the influence of individual-level characteristics. This is not to dismiss the importance of these factors in vendors' daily lives—extensive ethnographic research clearly demonstrates their significance (Anja & Zhang, 2023; Kamalipour, 2022). Rather, it indicates that when the fundamental spatial and economic foundation of a livelihood is destroyed, the specific form of state support becomes the primary determinant of recovery speed, potentially leveling pre-existing differentials based on policy design rather than individual traits.

This finding has important methodological implications for future research. It suggests that studies focusing exclusively on individual characteristics without accounting for policy design may miss crucial determinants of recovery outcomes. Furthermore, it highlights the potential of well-designed policy interventions to mitigate pre-existing inequalities—or conversely, of poorly designed interventions to create new forms of disadvantage that cut across traditional social divisions.

Our application of survival analysis to urban livelihood studies demonstrates significant methodological value. The technique’s ability to incorporate right-censored observations proved particularly important, as excluding vendors who had not yet recovered would have biased our understanding of recovery timelines, especially for higher-capital vendors. The comprehensive diagnostic testing—including proportionality checks, sensitivity analysis, and bootstrap validation—provides a robust framework for future applications of survival analysis in urban studies.

The moderate discriminative ability of our model (C-index = 0.645) also merits reflection. While confirming the importance of the factors we measured, it also suggests that unmeasured variables—perhaps related to vendor innovation, social networks, or locational characteristics—also influence recovery trajectories. This points to the need for mixed-methods approaches that can capture both the structural determinants quantified here and the agentive strategies that vendors employ in navigating post-relocation challenges.

Integrating our empirical findings with both theoretical frameworks yields important insights. The capabilities approach helps explain why mobile carts facilitate better outcomes: they restore what Sen terms “substantive freedoms”—the ability to pursue one's livelihood according to one's own reasoning and values. Meanwhile, the political economy lens illuminates why fixed stalls persist as a policy option despite their poorer outcomes: they align with state priorities of control, order, and formalization, even when these priorities conflict with vendor welfare.

Together, these frameworks suggest that successful urban policy for informal workers requires navigating the tension between state desires for spatial order and vendor needs for operational flexibility. Our findings indicate that policies that prioritize capability expansion—even if they complicate visions of orderly urban space—may yield superior economic outcomes while also enhancing human dignity and agency. This theoretical integration moves the discussion beyond technical policy evaluation toward deeper questions about urban citizenship, rights to the city, and the political construction of informality.

6. Conclusion

This study has systematically examined the temporal dynamics of income recovery among street vendors relocated from Purus Beach to Lapau Panjang Cimpago in Padang, Indonesia. Through survival analysis of longitudinal data, we have uncovered how differentiated policy interventions, vendor characteristics, and institutional contexts interact to shape post-relocation economic trajectories. This concluding chapter synthesizes our key findings and translates them into actionable policy recommendations while suggesting productive avenues for future research. By integrating our empirical results with the theoretical frameworks of Sen’s capabilities approach and the political economy of informality, we offer a comprehensive perspective on how urban development policies can better serve the needs of informal workers in secondary cities of the Global South.

Our analysis yields three particularly significant findings that challenge conventional wisdom about post-relocation recovery. First, the form of government assistance emerges as the most powerful determinant of recovery speed. Vendors receiving mobile carts recovered their pre-relocation income significantly faster—approximately twice as quickly—as those allocated fixed stalls. This finding remained robust across all statistical models, including Kaplan-Meier estimates, Cox regression, bootstrap validation, and sensitivity tests. The consistency of this result underscores the critical importance of spatial mobility and operational flexibility in vendor livelihood strategies.

Second, we identified a counterintuitive relationship between initial capital and recovery speed. Vendors with higher pre-relocation capital experienced slower income recovery—a finding that contradicts simplistic assumptions about the protective function of economic resources. This pattern suggests the existence of a “liability of embeddedness”, where vendors who were most successful in their original locations face particular challenges in transferring their business models to new environments. The sensitivity of this finding to censoring patterns further highlights the importance of methodological choices in capturing the full spectrum of recovery experiences.

Third, individual demographic and social characteristics—including gender, age, family support, and business experience—showed limited explanatory power in our multivariate models. This suggests that in contexts of profound structural disruption, institutional interventions and economic resources may override the influence of individual-level factors that might otherwise shape economic outcomes.

This study makes significant theoretical contributions by bridging normative and structural perspectives on urban informality. The capabilities approach has proven invaluable in explaining why mobile carts facilitate superior outcomes: they restore vendors’ substantive freedoms—particularly spatial agency and economic choice—that are essential for meaningful recovery. Meanwhile, the political economy framework helps explain the persistence of less effective policy options: fixed stalls align with state priorities of spatial order and control, even when they compromise vendor welfare.

The integration of these frameworks enables a more nuanced understanding of urban development conflicts. It reveals that the tension between mobile carts and fixed stalls represents not merely a technical choice between policy instruments, but a fundamental conflict between different visions of the city—one centered on vendor capabilities and livelihoods, the other on state control and aesthetic order. This theoretical synthesis moves the discussion beyond policy evaluation toward deeper questions about urban citizenship and the right to the city.

Based on our findings, we propose three key policy recommendations for urban development programs involving vendor relocation:

Relocation programs should provide flexible, mobile vending options as a first response to displacement. The demonstrated superiority of mobile carts in facilitating rapid recovery suggests they should be the default assistance option rather than the exception. Municipal governments should develop standardized, cost-effective cart designs that meet vendor needs while addressing legitimate public health and safety concerns.

Recognizing vendor heterogeneity is crucial for effective policy. Support should evolve from immediate, flexible relief to longer-term strategies that address diverse needs. For higher-capital vendors, this might include business development services and support rebuilding customer networks. For all vendors, secure tenure and adequate infrastructure in new locations remain essential for sustainable recovery. A one-size-fits-all approach is doomed to fail in the face of vendor diversity.

The stark contrast between policy effectiveness (carts) and policy preference (stalls) highlights the need for more inclusive governance. Municipal authorities should engage vendors as partners in planning relocation programs, from site selection to assistance design. Regular consultation mechanisms and vendor representation in decision-making bodies can help align state and vendor priorities, creating more legitimate and effective urban policies.

Our application of survival analysis to urban livelihood studies demonstrates several methodological advantages. The technique’s ability to handle right-censored data proved particularly important, as excluding vendors who had not yet recovered would have biased our understanding of recovery timelines. The comprehensive diagnostic testing—including proportionality checks and robustness validation—provides a template for future applications of these methods in urban studies.

The moderate predictive power of our models (C-index = 0.645) also suggests important directions for methodological innovation. Future research would benefit from mixed-methods approaches that combine survival analysis with qualitative investigations of the unmeasured factors—such as social networks, business innovation, and locational characteristics—that also shape recovery trajectories.

This study opens several productive avenues for future investigation. First, research could explore the long-term trajectories of vendor recovery beyond our observation period, examining whether the initial advantages of mobile assistance persist or diminish over time. Second, comparative studies across different cities could identify how varying governance arrangements and political contexts shape relocation outcomes. Third, investigation of the “liability of embeddedness” phenomenon could yield important insights for understanding how place-based success affects adaptability to new environments. Finally, research should examine the political and institutional factors that shape policy selection. Understanding why less effective policies persist despite evidence of their limitations represents a crucial frontier in the struggle for more just urban development.

This study has revealed a fundamental tension in urban development: the forms of assistance that yield the quickest economic recovery may not align with dominant visions of formal, orderly urban space. Navigating this tension requires moving beyond seeing informality as a problem to be eliminated and toward recognizing it as a dynamic economy to be integrated with justice and foresight. The ultimate measure of urban development should not be the elimination of informal livelihoods, but the expansion of substantive freedoms for all urban residents. As cities across the Global South continue to transform, our findings suggest that policies that prioritize human capabilities over spatial aesthetics, and vendor agency over state control, offer the most promising path toward genuinely inclusive urban development.

The data used to support the research findings are available from the corresponding author upon request.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Table A1. Interpretation of Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) results

Variable | VIF | 1 / VIF | Interpretation |

1.in_capital | 2.09 | 0.478 | No serious multicollinearity |

2.in_capital | 2.21 | 0.453 | Safe, though slightly higher |

1.gov_help | 1.11 | 0.900 | Very safe |

age | 1.33 | 0.752 | Safe |

1.family_help | 1.09 | 0.915 | Safe |

2.family_help | 1.11 | 0.899 | Safe |

1.gender | 1.03 | 0.967 | Very safe |

2.lob | 1.29 | 0.778 | Safe |

Notes: The model shows no signs of multicollinearity. All predictor variables can be interpreted reliably and stably in your Cox Regression model.

Table A2 Cox proportional hazards estimates (HR)

Variable | x1 | x2 | x3 | x4 | x5 | x6 | x7 |

1.in_capital | 0.8690 | 0.8706 | 0.8892 | 0.8761 | 0.8792 | 0.9130 | 0.8823 |

(SE) | (0.30) | (0.30) | (0.31) | (0.32) | (0.32) | (0.32) | (0.33) |

2.in_capital | 0.5670 | 0.4416** | 0.4516** | 0.4503** | 0.4496** | 0.4684* | 0.4538* |

(SE) | (0.37) | (0.38) | (0.39) | (0.40) | (0.40) | (0.41) | (0.41) |

1.gov_help | 2.0591** | 2.0365** | 2.0407** | 2.0413** | 2.1803** | 2.1444** | |

(SE) | (0.30) | (0.30) | (0.30) | (0.30) | (0.31) | (0.31) | |

age | 1.0031 | 1.0026 | 1.0026 | 0.9981 | 1.0033 | ||

(SE) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | ||

1.family_help | 1.1689 | 1.1577 | 1.2732 | 1.2568 | |||

(SE) | (0.42) | (0.42) | (0.44) | (0.44) | |||

2.family_help | 1.0310 | 1.0195 | 1.0062 | 1.0306 | |||

(SE) | (0.27) | (0.28) | (0.28) | (0.29) | |||

1.gender | 0.9469 | 0.9767 | 0.9501 | ||||

(SE) | (0.27) | (0.28) | (0.28) | ||||

lob | 0.7822 | ||||||

(SE) | (0.30) | ||||||

N | 103 | 103 | 103 | 103 | 103 | 103 | 103 |

Notes: Significance levels: p < 0.1 (*), p < 0.05 (**).

Table A3. Model discrimination: Harrell’s concordance statistic

Number of subjects (N) = 103 |

Number of comparison pairs (P) = 2578 |

Number of orderings as expected (E) = 1662 |

Number of tied predictions (T) = 2 |

Harrell’s C = (E + T/2) / P = 0.6451 |

Somers’ D = 0.2901 |

Following the estimation of the Cox proportional hazards model, the model’s discriminative ability was assessed using Harrell’s C-statistic (concordance index). The analysis yielded a concordance value of 0.6451, indicating that the model has a moderate capacity to correctly rank individuals based on their predicted risk of income recovery. Specifically, this implies that in approximately 65% of all possible subject pairs, the model accurately.

Figure A1. Kaplan-Meier failure estimates

Figure A2. Failure curves by government assistance

Figure A3. Log-Log survival curves

Table A4. Interpretation of Schoenfeld residual test results

Variable | rho | Chi2 | p-value | Interpretation |

1.in_cap | -0.17015 | 2.22 | 0.1364 | PH assumption holds (not significant) |

2.in_cap | -0.10278 | 0.79 | 0.3749 | PH assumption holds |

1.gov_help | 0.23453 | 3.59 | 0.0581 | Borderline, but still not significant |

age | -0.01941 | 0.02 | 0.8763 | PH assumption holds strongly |

1.family_help | -0.00172 | 0.00 | 0.9883 | PH assumption clearly holds |

2.family_help | -0.03403 | 0.08 | 0.7788 | PH assumption holds |

1.gender | -0.14293 | 1.52 | 0.2178 | PH assumption holds |

2.lob | -0.16301 | 1.82 | 0.1776 | PH assumption holds |

Notes: Global test: Chi2 = 9.34, df = 8, p = 0.3145 → No violation of the overall PH assumption.

Figure A4. Schoenfeld residuals for gov_help

Table A5. Comparison of cox regression results: Full sample vs. event-only sample

Variable | HR (Full Data) | p-value (Full) | HR (Event Only) | p-value (Event Only) |

Initialcapital (Middle) | 0.823 | 0.548 | 0.887 | 0.709 |

Initial capital (High) | 0.359 | 0.012 | 0.581 | 0.205 |

Gov. assistance (1) | 2.218 | 0.008 | 2.342 | 0.004 |

Age | 1.010 | 0.436 | 1.008 | 0.528 |

Family help (1) | 1.225 | 0.633 | 1.012 | 0.977 |

Family help (2) | 1.113 | 0.702 | 0.768 | 0.378 |

Gender (Male) | 0.886 | 0.661 | 0.878 | 0.641 |

Length of business (lob) | 0.740 | 0.296 | 0.786 | 0.405 |

Table A6. Bootstrap cox proportional hazards regression results (1,000 replications)

Variable | HR | Bootstrap Std. Err. | z | p-value | 95% Confidence Interval |

Government assistance (1) | 2.218 | 0.664 | 2.66 | 0.008 | 1.234–3.988 |

Initial capital (1: Middle) | 0.823 | 0.267 | -0.60 | 0.548 | 0.436–1.554 |

Initial capital (2: High) | 0.359 | 0.146 | -2.52 | 0.012 | 0.162–0.797 |

Age (continuous) | 1.010 | 0.012 | 0.78 | 0.436 | 0.986–1.034 |

Gender (1: Male) | 0.886 | 0.245 | -0.44 | 0.661 | 0.515–1.523 |

Family help (1) | 1.225 | 0.519 | 0.48 | 0.633 | 0.533–2.812 |

Family help (2) | 1.113 | 0.312 | 0.38 | 0.702 | 0.643–1.928 |

Length of business (lob) | 0.740 | 0.214 | -1.04 | 0.296 | 0.420–1.302 |