Acadlore takes over the publication of JCGIRM from 2022 Vol. 9, No. 2. The preceding volumes were published under a CC BY license by the previous owner, and displayed here as agreed between Acadlore and the owner.

How Organisational Performance is Affected by Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)

Abstract:

This paper aims to report as a study that contributes to the understanding of the roles of strategic corporate social responsibility (CSR) in overall organisational performance. The approach to the paper was by the review of acclaimed researches with linkages between corporate social responsibility, more specifically strategic corporate social responsibility and organisational performance. Strategic CSR undertaken by various organisations were analysed to find how significant they affect to performance metrics. The researchers had difficulties unearthing previous tangential and empirical research as there had not been a wealth of research in the area of CSR relationships especially with regards to strategic CSR practices and performance and at the same time, previous research on CSR mostly focuses on its nature and impact on society and how customer loyalty can be gained with CSR. The study thus revealed that, although some organizations to some extent confuse CSR with philanthropic reasoning, they are aware of how rewarding it is for both societal stakeholders and the firm and intensively work towards integrating CSR with other business undertakings. This research contributes to one’s understanding of the impact that strategic CSR has on organisational performance when instituted in the business. Additionally, the study analyses how business performance may be affected either positively or negatively depending on the level of integration that strategic CSR has been implemented by organisations. The outcome of the study ultimately, will help top level management to amend shortcomings by implementing strategic CSR techniques as well as build formidable business performance.

1. Introduction

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) is a concept that has attracted worldwide attention and acquired a new meaning in the global economy. Intense interest in CSR in recent years has stemmed from the advent of globalization and international trade, which has reflected in increased business complexity and new demands for enhanced transparency and corporate citizenship. According to Ullmann (1985), CSR by no means is a new issue. This would indicate that corporations undertaking social responsibility are not a new phenomenon. Nevertheless, CSR is more in the spotlight now than ever, since multinational corporations’ power over world economy is stronger than ever and subsequently with that, society’s demands on social and environmental responsibility (Forsberg, 2003). Martin (2002) accentuates that globalization also heightens society’s anxiety over corporate conduct; as such companies need to satisfy not only stockholders but also those with less explicit or implicit claims (McGuire, Sundgren and Schneeweis 1988). This is known as the stakeholder theory described by Enquist, Johnson and Skålén (2005) as a strategy that does not separate ethics from business, and argues that the needs and demands of all stakeholders must be balanced.

CSR is prevalent and on a wide range of issues, corporations are encouraged to behave socially responsibly (Engle, 2006). Generally, the belief that profit maximisation is management’s only legitimate goal is seen as one end of a continuum, while at the other end is the argument that businesses are the trustees of societal property that should be managed for the public good (Ofori and Hinson, 2007). Besides, corporate governance has evolved from the traditional ‘‘profit-centred model’’ to a ‘‘socially responsible model.’’, entreating organizations to become more sensitive to the CSR concept.

2. Defining Corporate Social Responsibility

Meijer and Schuyt, (2005) defined CSR as social responsibility of business that encompasses the economic, legal, ethical, and discretionary (philanthropic) expectations that society has of an organization at a given point in time. Wood (1991) also stated a definition of CSR as a business organization’s configuration of principles of social responsibility processes of social responsiveness, and policies, programs and observable outcomes as they relate to the firm’s societal relationships.

However, the often cited definition in literature comes from the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD) which first defined the concept of CSR in 1999 as “The commitment of business to contribute to sustainable economic development, working with employees, their families, the local community and society at large to improve their quality of life”. Later in 2000, the WBCSD revised or redefined CSR as “the continuing commitment by business to behave ethically and contribute to economic development while improving the quality of life of the workforce and their families as well as the local community and society at large”.

The salient features in these definitions are that society expects businesses to voluntarily integrate social and environmental concerns in their business activities and in their relations with their stakeholders, and to carry out their operations in an ethical manner within the legal framework in a sustainable and profitable manner, and at the same time contribute in solving society’s numerous problems (Danko et al., 2008). Moreover, the definitions and clarifications for CSR shows that CSR implementation is all- inclusive and must be assimilated with the core business strategy for addressing social and environmental impacts of businesses. CSR also needs to address the well-being of all stakeholders and not just the company’s primary shareholders. Further, philanthropic activities are only a part of CSR, which otherwise constitutes a much larger set of activities entailing strategic business benefits.

Corporations are therefore expected to properly balance the different economic, legal, ethical and social responsibilities they confront in the business environment, and in certain situations voluntarily go beyond their immediate financial interest and the mere compliance with mandatory obligations of the legislation (Halme et al., 2009). This is however contrary to Friedman’s (1970) famous argument that there is one and only one social responsibility of business; and that duty is to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game.

3. Theoretical Literature

In addressing the CSR phenomenon, various researchers have employed a variety of complex theories and approaches. Garriga and Mele (2004) classified them into four main types of theories, namely, instrumental theory, political theory, integrative theory and ethical theory. A number of approaches are further identified under each of the four classified theories. For instance, within the ethical theories, the authors identified normative stakeholder, universal rights, and sustainable development as the common good approaches to CSR. However, the most commonly employed approaches in CSR discourse are the legitimacy approach from the political theory (Branco and Rodrigues, 2006) and the stakeholder approach from both the integrative and ethical theories (Friedman and Miles, 2006).

The legitimacy view holds that society legitimises the activities of an organisation by its perception that the firm’s activities are desirable, proper or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs and definitions (Kunetsov et al., 2009). Slim (2002) succinctly defines it as a particular status with which an organisation is imbued and perceived at any given time that enables it to function with general consent of people, their groups, formal and informal organisations and governments that constitute the social environment in which it operates. It therefore presupposes that organisations seen to be actively socially responsible in their activities are legitimising their operations and positions within the business environment. Because of the understanding that compliance with societal expectations is vital to building up reputation and legitimising firms’ activities, the theory posits that, organisations will therefore make a rational and strategic response to these societal expectations in the pursuit of profits (Kunetsov et al., 2009).

The legitimacy view is underscored by the widely cited findings that society tends to reward organisations that are considered to be socially responsible in various ways. For instance, Du et al. (2010) observed that evidence from academic research and marketplace polls suggested that key stakeholders such as consumers, employees and investors are increasingly likely to reward good corporate citizens and punish bad ones. This might involve consumer loyalty and resilience to negative company news, willingness to pay premium prices for the company’s products or services, customers switching from another company’s product to patronising the products of the company associated with good cause, and probably publicising by word-of-mouth the company’s products (Arli and Lasmono, 2010).

The stakeholder theory argues that organisations have constituents (e.g. shareholders, customers, suppliers, employees, local communities, the government and the general public) who need to be well managed in order to retain their interest and participation in the organisation to ensure the survival and continuing profitability of the corporation (Clarkson, 1995). The theory therefore suggests that organisations are in a constant association with these stakeholders and that the success and performance of companies depend on their ability to maintain trustful and mutually respectful relations with the various stakeholders (Kunetsov et al., 2009).

Hence the stakeholder theory seems similar in perspective to the legitimacy theory. The connection that can be drawn from the stakeholder and legitimacy theories is that the trust, as mentioned in stakeholder theory from stakeholders of organisations depends on the extent to which society, which is also a stakeholder, sees the firm’s activities as desirable and legitimate as identified as essential in the legitimacy theory. In principle, the legitimacy theory holds the stakeholder theory but it’s worth noting that both theories also underscore the importance of business and society working together not only to help solve some societal problems but also create and maximise both economic and social value. This view is captured by the strategic social and competitive investment theory (Porter and Kramer, 2002) and the CSR Value Chain Model.CSR has increasingly provided the focus for examining broad philosophical questions about the roles and responsibilities of companies and their relationship with the roles and responsibilities of government and other stakeholders. Carroll (1991) highlights these roles and responsibilities of companies and broadly categorised them as economic (to be profitable), legal (to obey the law), ethical (to do what is right, just and fair), and philanthropic (to contribute some of a firm’s resources to society to improve the quality of life).

However Lantos, 2002, suggests three different types or roles of CSR that organisations can practice namely, Ethical CSR (to do what is morally mandatory and this goes beyond fulfilling a firm’s economic and legal obligations but also its ethical responsibilities to avoid societal harm), Altruistic CSR (this is any activity that involves contributing to the good of various societal stakeholders, even if this sacrifices part of the business’s profitability), and Strategic CSR (which is caring corporate community service activities that accomplish strategic business goals) or plainly, good works that are also good for the business.

Ethical CSR is justly obligatory and goes beyond fulfilling a firm’s economic and legal obligations, to its responsibilities to avoid harm or social injuries, even if the business might not benefit from this. Lantos, 2001 argues that there is nothing especially commendable about this level of fulfilment of social responsibilities since it is what is ordinarily expected in the realm of morality. Ethical CSR therefore involves a comprehensive effort by organisations to avoid and correct activities that injure others in the society. Ethical CSR fundamentally entails fulfilling the firm’s ethical duties and obligations. This is a social responsibility of businesses in the sense that an organisation is morally responsible to any individuals or groups (stakeholders) where it might inflict actual or potential injury (physical, mental, economic, spiritual and emotional) from a particular course of action. Even when the two parties to a transaction are not harmed others parties might be and as such it is inscribed on organisations to ethically conduct their business operations in a manner that is safe and not hazardous to the society they operate in and also beyond its confines.

Ethical statutes such as corporate philanthropy, environmental policies and worker rights policies must be adhered to even if it will be at the firm’s expense as they are necessary moral standards and therefore must override organisational self-interest. Occasionally certain actions need to be undertaken not for their profitable but because fundamentally they are right things to do. Managers of organisations do not enjoy a blatant obligation to only maximize profits and other benefits for shareholders whilst showing obvious disregard to the means used in attaining these performance boosts. As in all social responsibility decisions, there are trade-offs, and with ethical CSR it is often between short‐run profitability and moral actions and as such managers have to make profits whilst also working within the confines of ethicality. For instance, money spent on product safety or pollution control might reduce shareholder profits, but the alternative is to threaten unethically the welfare of others in society (Boatright, 1999). Another key example is the decision of various telephone companies in many countries to avoid charging calls made to emergency service numbers.

Lantos, 2001 succinctly examines altruistic or humanitarian CSR as an “interest in doing good for society regardless of its impact on the bottom line”. He observes that this type of CSR demands that corporations help alleviate public welfare deficiencies such as the proliferation of illegal drugs, poverty, crime, illiteracy, underfunded educational institutions and chronic unemployment. Whereas, economic, legal and ethical obligations are mandatory, philanthropic responsibility is desired by society, that is, it is optional in that it is not expected with the same degree of moral force (Carroll, 2001) since corporations are not causally responsible for the deficient conditions they are attempting to rectify.

It has been argued that CSR is most honourable when it fulfils altruistic roles in society. Altruistic (humanitarian, philanthropic) CSR involves contributing to the common good at the possible, probable, or even definite expense of the business. Humanitarian CSR has firms go beyond preventing or rectifying harms they have done (ethical CSR) to assuming liability for public welfare deficiencies that they have not caused (Lantos, 2001). This constitutes actions and activities that morality does not dictate but are beneficial for the firm’s stakeholders although not it may not be necessary or profitable for the company. It is probably for this reason that altruistic CSR is relatively rare (Smith and Quelch, 1993).

Strategic CSR happens when a firm undertakes its social welfare responsibilities but also create value for the organisation. It creates a win‐win situation in which both the corporation and one or more stakeholder groups benefit from the CSR activities that will be embarked on. Through strategic CSR, corporations can assume their social responsibilities with the knowledge and believe that it will be in their best financial interests to do so. Carroll (1979) points out that the economic and societal interests of the firm are often intertwined; for example, product safety is of concern both at the economic and societal levels therefore by integrating CSR into core business processes and stakeholder management, organizations can achieve the ultimate goal of creating both social value and corporate value.

The stakeholder-driven perspective highlights the importance of how an organisation’s strategic CSR activities can influence its stakeholders to promote some positive and rewarding behaviours (e.g. seeking employment with the company and investing in the company) towards the firm (Du et al., 2010). CSR also plays a significant role in the maximisation of shareholders’ wealth through the attraction of investment capital and the increase of share prices on the stock markets (Michael, 2003; Sen et al., 2006). Investing in a socially responsible way attracts investment funds faster than the broader universe of investment opportunities under professional management (Danko et al., 2008). Hence, companies will benefit broadly from cost and risk reduction, reputation and competitive advantage, and create a win-win situation through synergistic value creation if they engage in CSR (Lindgreen and Swaen, 2010).

According to Callan and Thomas (2009), Margolis and Walsh (2003) observed in at least 127 empirical studies that examined the relationship between socially responsible companies and their financial performance, that were published between 1972 and 2002 that a majority of the studies reported a positive relationship between the two variables. Orlitzky et al. (2003) also did an in-depth analysis of 52 studies on the relationship between the level of companies’ CSR activities and their financial performance and reported a positive relationship between them. In particular, they found a positive association between CSR and organisational performance across industries and across study contexts. Furthermore, they underscored that the universally positive relationship varies (from highly positive to modestly positive) because of contingencies, such as reputation effects, market measures of organisational performance, or corporate responsibilities disclosures. Essentially, they emphasised the existence of a positive cycle between CSR and corporate performance, and they suggested the use of CSR as a reputational and competitive tool. Porter and Kramer (2002) further reveal that engaging in CSR can often be the most cost-effective way, and sometimes the only way, to improve the firm’s competitive context and maximise both social and economic benefits.

The case can therefore be made that firms see a strategic value in being socially responsible as CSR activities give them legitimacy to operate in an acceptable and profitable manner. As a result, it is arguable that although firms could engage in CSR purely on moral or ethical grounds, they normally do so to build up reputation and enhance corporate profit or shareholder gain (Kunetsov et al., 2009).

More recently, Van Beurden and Gössling (2008) presented their meta-analysis of 34 papers. They considered literature published after 1990 primarily because they wanted to gain an insight into recent works involving CSR and organisational performance, which are more likely to have overcome methodological flaws, and secondly, because these papers were published in an era where the social role of businesses are discussed, analysed and scrutinized in a new light, as organisations continually assimilate CSR activities in their strategy formulation and implementation. The results of this review presents 68% of the studies showing a positive corporate social activity – corporate business performance relationship, 26% showing no significant relationship and only 2% showing a negative relationship.

Wang and Choi (2010) focused on the moderating effect of CSR consistency on business performance. In particular, they hypothesised that not only is organisational performance influenced by the level of CSR, but also by its temporal consistency (that is, the reliability of a firm’s treatment of its stakeholders over time) and inter-domain consistency (that is, the consistency in a firm’s treatment of its different stakeholder groups). The specifically created variables were found to have a positive moderating effect on the CSR-Performance relationship.

Michelon et al. (2012) specifically concentrated on a construct, defined as “Strategically Prioritized CSR activities”, that was found to have a greater effect on organisational performance (both accounting-based and market-based measures) than a generic approach to CSR unrelated to company’s strategy. These results are consistent with Porter and Kramer (2006) concept of Strategic CSR and with the Stakeholder Theory discussed before.

All these empirical analyses seem to suggest a positive and increasingly consistent relationship between CSR and organisational performance, although it must be noted that there are still some detractors.

Past studies have shown that as many as 80 different measures can have been used to measure the performance of a firm. Metrics such as firm size, return on assets (ROA), return on equity, asset age and return on sales are most frequently used to measure financial performance, particularly, ROA which is consistently claimed to be an authentic measure of financial performance. Unlike other accounting measures such as return on equity or return on sales, ROA is not affected by the differential degree of leverage present in firms. Because ROA is positively correlated with the stock price, a higher ROA implies higher value creation for shareholders.

Financial performance measures are lag indicators and authors suggest that traditional financial performance measures are historical in nature (Dixon et al., 1990) and performance arising from mostly tangible assets. They often fail to properly record performance from intangible assets such as customer relationships, employee satisfaction, innovation, investment in research and development, and like that have become significant sources of competitive advantage for firms in recent times. In contrast, Non- financial performance measures focus on a firm’s long term success factors such as research and development, customer satisfaction, internal business process proficiency, innovation, and employee satisfaction, and capture performance improvements from intangible assets. Investments in intangible assets, such as research and development are expensed immediately instead of getting capitalized in the traditional accounting system. Such treatment depresses the profit in the current year though benefits from such investments accrue to the firm over a long period of time. By accounting for such performance improvements, not-for-profit measures provide indirect indicators of firm performance. Because of their focus on consequences rather than causes of performance, non-financial performance measures are considered as ‘lead indicators’. Financial performance measures are objective in nature whereas non- financial performance measures are subjective in nature that includes manager’s perception of firm performance on market share, employee health and safety, investment in research and development and others. Hence, financial measures along with non-financial performance measures are used to assess firm performance historically.

The relations between CSR and firm performance are mostly inconclusive, but positive relations between the two have been reported in most of the studies (Margolis and Walsh, 2003) suggesting an instrumental orientation of CSR initiatives. A strategic instrumental orientation towards CSR suggests the alignment of the social goal with the business goal where CSR is considered as a strategic tool to promote the economic objective of the firm. Managers foresee significant value additions in firm performance due to strengthened stakeholder relations. Management theorists argue that by improving CSR toward stakeholders, firm performance is augmented (Waddock and Graves, 1997).

The influence of stakeholder-oriented CSR on firm performance can be understood with the help of three theories: (a) consumer inference making, (b) signalling theory, and (c) social identity theory. Consumer inference making theory suggests that if consumers knows that the manufacturer of the product is a responsible firm, they can infer positively about the product (Brown and Dacin, 1997). Such inferences induce consumer goodwill (Brown and Dacin, 1997) that influences purchase intention. Signalling theory suggests that in situations where there is information asymmetry between buyers and sellers, consumers look for information and signals that distinguish companies performing well on attributes of interest compared to companies performing poorly (Kirmani, 1997). Signals such as warranties indicating reliability and higher quality of products enable consumers to decide between companies. Consumers associate higher product quality with proactive corporate citizenship (Maignan and Ferrell, 2001) and potential job-seekers value CSR record of companies as a signal for organizational attractiveness (Greening and Turban, 2000). Social identity theory emphasizes that one’s self-concept is influenced by membership in different social organizations, including the company for which an individual works (Dutton et al., 1994). Employees’ self-image is influenced by the image and reputation of their employers, consumers identify themselves with organizations or brands involved in discretionary citizenship and institutional investors like to be associated with socially responsible firms (Graves and Waddock, 1994). Such bonds of identification encourage positive evaluations of a firm’s products, and reap value addition through customer loyalty, advocacy, positive words-of-mouth, and resilience to negative brand information (Sen et al., 2006).

Alternatively, irresponsible behaviour by firms agitates stakeholders. They often react by boycotting the company reducing consumption of the company’s products, initiating legal action against the company, and may also spread bad words-of-mouth about irresponsible business practices. Boycotting of Nike products due to human rights’ abuse and unsafe working conditions at suppliers’ locations in Asia (Herbert, 1996), or sharp reaction from environmentalists and consumers to the pesticide content in Pepsi and Coca-Cola beverages in India (Financial Express, 2006) are few such instances. While improved stakeholder relations have the potential to improve a firm’s reputation and performance, strained relations have the risk of adversely affecting a firm’s performance.

The relation between CSR and financial performance has been investigated in theoretical and empirical studies by various researchers on CSR (Margolis & Walsh 2003) as well as their sustainability (Schaltegger and Synnestvedt 2002). Empirical research on strategic CSR and financial performance can be divided into qualitative and quantitative research.

Qualitative research in this area mainly uses case studies or best practice examples to investigate the influence of CSR on competitiveness. For example, Argenti (2004) presented an in-depth case study of Starbuck’s collaboration with several NGOs deriving lessons for successful business-NGO partnerships. Rondinelli and London (2002) presented several examples from business practice to support their analysis of benefits from cross-sectorial environmental collaborations.

Although most of these studies do not explicitly focus on the business case for CSR, they often provide valuable insights about strategic CSR benefits. Three main methods are used in quantitative empirical research in this area (Salzmann et al. 2005). These are;

I. Portfolio studies (E.g. Comparing portfolios of environmentally and socially proactive and reactive companies.)

II. Event studies (E.g. Investigating market responses after CSR-related events) and

III. Multiple regression studies.In their discussion of portfolio, event, and multiple regression studies investigating the relation between CSR and financial performance Salzmann et al. (2005) found inconclusive results. Similarly, Wagner et al. (2001) found mixed results in their meta-study of quantitative empirical research analysing the relationship between environmental and economic performance. Margolis and Walsh (2003) conducted a meta-investigation of 127 multiple regression studies that analyzed the relationship between Corporate Social Performance and Corporate Financial Performance between 1972 and 2002. Although they also found mixed results, the authors concluded that a positive relationship predominated. However, they criticized the inconsistent use of variables and methodologies used in the research.

Concerning theoretical research in this area, sustainability researchers often argue that the relationship between economic performance and ecological or social performance follows an inverse U-shaped curve (Schaltegger and Synnestvedt 2002, Steger 2006). That relationship could explain the mixed results found in empirical studies as CSR could have positive as well as negative effects on financial performance depending on the individual position of a company on the curve (In their empirical study of the EU manufacturing industry, Wagner and Schaltegger (2004) tested the hypothesis of an inverse U-shaped relationship between environmental and economic performance. They found that for companies pursuing a strategy-oriented environmental responsibility towards shareholder value had a relationship that was stronger than for firms without such a strategy. From these results, the impact of CSR on economic performance seems to be dependent on the individual company strategy.

Although current researches analysing the link between CSR and financial performance seem to provide some support for the existence of a business case for CSR, the studies do not help managers in evaluating their CSR involvement on a company- or even project-specific level.

Corporate Social Responsibility is an opportunity for companies to improve social welfare as well as maximize profit but is there a non-western brand of CSR or is it an imitation of western CSR practices? Although some researchers have attributed the similarities between western and non-western CSR practices to early exposure to western culture via colonialism (Dartey-Baah and Amponsah-Tawiah, 2011)., other scholars argue from a public perspective stated that a CSR strategy should be designed to fit the social system and reflect the national business of home countries (Smith,2003). Atuguba and Dowuona-Hammond (2006) adds that while certain fundamentals of CSR remain the same, CSR issues vary in nature and importance from industry to industry and from location to location and different emphases are made in different parts of the world. CSR is most commonly associated with philanthropy or charity in developing countries, in this case the non-western territories, i.e. through corporate social investment in education, health, sports, development, the environment, and other community services (Visser 2007). However, the current understanding and practice of CSR in Western economies is argued to have ‘advanced’ beyond philanthropy (Amaeshi et al, 2006). The difference in how CSR is perceived and practices between the west and non-western countries is attributed to certain drivers. A case in point is Nigeria, where the practice of CSR is said to be still largely philanthropic. Amaeshi et al (2006) propose that Nigeria’s perception and practice of CSR is framed by socio-cultural influences like communalism, ethnic religious beliefs, and charitable traditions. Other drivers within the non-western countries identified by (Dartey-Baah and Amponsah-Tawiah, 2011) include political reform, socio- economic priorities, governance gaps, market access and international standardization among others. In the views of Phillip (2006) unlike the USA and Europe, where government pressure on MNCs has gone a long way in shaping CSR initiatives, Africa’s motivation for CSR comes from the institutional failure of the government. Contrary to the non-western claims, Löhman and Steinholtz (2004) noted the main CSR driver in the western countries to be the customer who represents one of the primary and essential stakeholder groups for firms. It is worth mentioning that the inability of government to provide amenities for its citizens accentuates the roles of multinationals in CSR and philanthropy is not regarded as CSR in Western countries (Frynas, 2009).

A number of studies have found that CSR varies not only in terms of its underlying meaning, but also in respect to the CSR motives of firms across countries. In order to understand how CSR is perceived and practice by multinational firms operating in the non-western territories, Valor, (2005) affirms how doing the right thing is important and valuable to organizations especially for global organizations, and are essential for defining global reputation and brand (Lewis, 2003). Owing to this ideology, firms especially multinational corporations’ CSR activities are translated into strategic benefits thus making CSR a strategic branding tool, but only when communicated with stakeholders (Morsing, 2006). Developing global CSR activities in itself is a complicated challenge, as organisations have to deal with social issues within each domestic environment of operations (Aruthaud-Day,2005)., making the firm responsible to both international and domestic stakeholders. This assertion however contradicts Husted and Allen (2006) view on how global organizations tend to focus more on country specific social issues, rather than global social issues. Consequently, it is important to highlight the interactions between strategic CSR and international business performance. That is to understand to what extent organizations can effectively undertake global CSR activities across all internal and external activities. There have been criticisms in regards to inconsistencies that exists in the global CSR related activities of multinational corporations but to eliminate these challenges Velaz et al., (2007) posited that Global organizations that choose to adopt a broad corporate responsibility ethos must have a way of ensuring that these values are incorporated into all global activities. In this way responsibility becomes one of the distinctive features of the global organization and drives corporate actions and image towards the enhancement of the desired international business performance.

CSR can contribute to business performance but only to the extent that various CSR practices fit stakeholders’ expectations and needs of the society in which they are operating. Different social norms and cultural values contribute to the attainment of different business benefits in contrasting cultural contexts. Investigating how different types of CSR practices may have greater or lesser impacts on business outcomes in different culture, a recent study by Lo et al. (2008) found that while customer and employee CSR was positively related to the corporate reputation of firms in China, these CSR practices were not significantly related to the corporate reputation of firms in the United States.

By taking a strategic approach to CSR, companies can determine what activities they have resources to devote to whilst still being socially responsible and can choose those actions and make decisions which will garner value from these undertakings whilst strengthening their competitive edge. By development CSR as part of a company’s overall plan, organizations can ensure that profits and increasing shareholder value do not overshadow the need to behave ethically to their stakeholders.

Apart from internal drivers such as standards and belief, some of the key stakeholders that influence corporate behaviour include governments (through instituted laws and regulations), investors and customers. A key stakeholder in this regard is the community within which organisations operate, and many companies have started realizing that the ‘license to operate’ is no longer given by governments alone, but communities that are impacted by a company’s business operations. Adapting strategic CSR programmes that meet the expectations of these communities do not only provide businesses with the license to operate without stakeholder hostility, but also to maintain the license, thereby precluding any trust and image deficit that.

Several human resource studies have linked a company’s ability to attract, retain and motivate employees with their CSR commitments. Interventions that encourage and enable employees to participate are shown to boost employee morale and encourage a sense of belonging to the

Certain innovative strategic CSR initiatives emerging entails companies investing in enhancing community livelihood by incorporating them into their supply chain. This has benefitted these communities through the provision of safe and reliable employment ventures and will cause a steady increase in their income levels while providing the companies with additional locally-competent and secure supply chain.

The traditional benefit of generating goodwill, creating a positive image and branding benefits continue to exist for companies that operate effective CSR programmes; most especially strategic CSR because this creates return value for the organisations by aiding them to position themselves in stakeholder memory as responsible corporate citizens. A functional, easily-identified-with corporate identity and image cannot be trifled with as it conveys an organization’s ideals, motives and objectives – an essential mix of what an organisation is about. The advantage of creating a consistent and functional corporate image is that it ensures the organisation is easily recognized, remembered and respected by its stakeholders.

Business benefits and effects that are derived as a result of implementing strategic CSR activities have been analyzed into these 5 main areas.

Positive effects on company image and reputation: Image represents ‘‘the mental picture of the company held by its audiences’’ (Gray and Balmer 1998,), which is influenced by communication messages. Reputation builds upon personal experiences and characteristics and includes a value judgment by a company’s stakeholders. Whereas image can change quickly, reputation evolves over time and is influenced by consistent performance and communication over several years. As a result, both image and reputation can influence company competitiveness (Gray and Balmer 1998). Schwaiger (2004) found in his empirical research that CSR could influence reputation. The Harris-Fombrun Reputation Quotient equally includes CSR as one dimension influencing company reputation (Fombrun and Wiedmann 2001).

Iwu-Egwuonwu, (2011) explains that, company reputation allows organisations to charge premium prices for their products and services and customers will prefer to patronize the products and services of the reputable company even when other company’s products are available at comparable quality and price. Furthermore, a reputable company is valued in the financial market and its stocks are also valued higher in the capital markets and as such in periods of controversy stakeholders will support the company and lastly benefits the organisations in periods when they want to needed capital for projects.

Positive effects on employee motivation, retention, and recruitment: On the one hand, effects in this area can result from an improved reputation. On the other hand, strategic CSR can also directly influence employees as they might be more motivated working in a better working environment or draw motivation from the participation in CSR activities that do not only provide altruistic value for the community but return-on value for the organisation and all its all stakeholders, such as the employees themselves. Similarly, CSR activities can directly or indirectly affect the attractiveness of a company for potential employees. This allows the company to be able to attract more competent and skilled personnel into the organisation workforce, hereby marginally increasing the business’ efficiency and work rate; a necessary recipe to exceed its customers’ expectations and to garner more returns such as profits and customer loyalty.

Cost savings: Cost savings have been extensively discussed in sustainability research. For example, Epstein and Roy, 2001 argued that efficiency gains could result from a substitution of materials during the implementation of a sustainability strategy, improved contacts to certain stakeholders such as regulators resulting in time savings, or improved access to capital due to a higher sensitivity of investors to sustainability issues. Cost savings denote less net organisational expenditure and increased net profitability, thereby allowing the organisation to invest in more innovative and profitable ventures.

Revenue increases from higher sales and market share: Often, researchers argue that CSR can lead to revenue increases. These can be achieved indirectly through an improved brand image or directly such as a CSR-driven product or market development. Increased revenues and market shares facilitates the organisation being able to generate faster return on investments, increased innovation to support continued delivery of competitive advantage or improvement in the value of service provision. Not forgetting that improving staff motivation, retention, and their contribution and ultimately maximizing their potential can also be tied intricately into steady revenue generation.

CSR-related risk reduction or management: CSR can also be used as a means to reduce or manage CSR- related risks such as the avoidance of negative press or customer/NGO boycotts. The reduction or absence of such risks permits firms to operate at their optimum levels whilst supporting strategic business planning, allowing for the effective use of all resources, facilitating the promotion of continuous improvement and the advantage to make a quick grasp of new opportunities. It also provides a stable means to absorb the fewer shocks and unwelcome surprises that may arise and most importantly reassuring stakeholders about the business’ sustainability in its operation reciprocating in more investments from stakeholders.

These five clusters of CSR business benefits are similar to the of value drivers of sustainability. Schaltegger and Wagner (2006) theoretically identified five main effects to organisations from tackling environmental and social issues, they include direct financial effects (e.g., fines, charitable contributions); market effects (e.g., customer retention); effects on business and production processes (e.g., lower production costs); effects on learning and organizational development (e.g., employee motivation, innovation); non-market effects (e.g., less stakeholder resistance towards production facilities).

4. Conceptual Framework

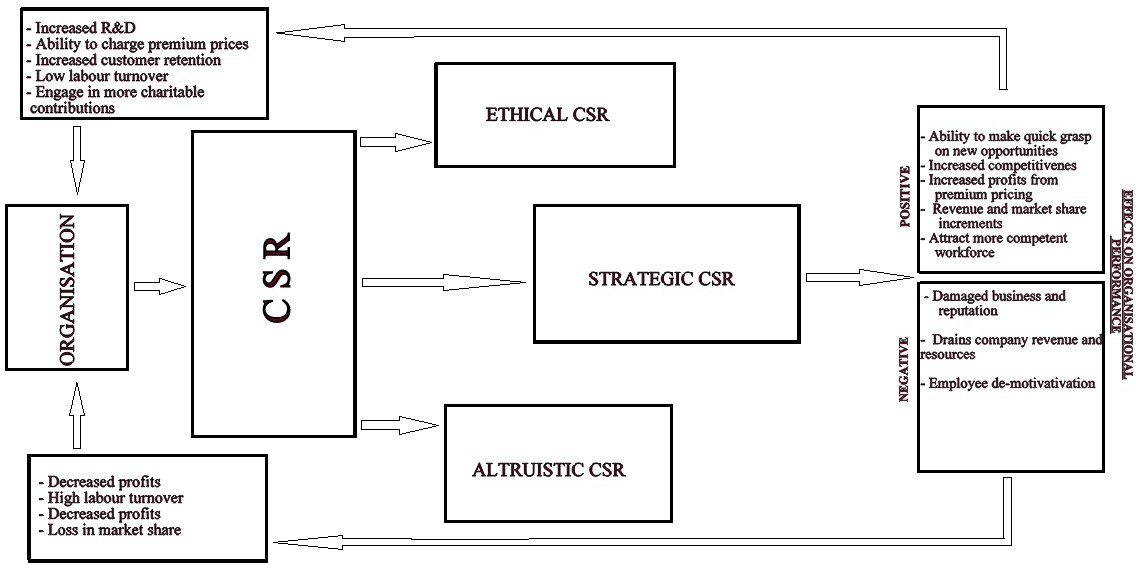

If corporations were to analyse their opportunities for social responsibility using the same frameworks that guide their core business choices, they would discover that CSR or more specifically strategic CSR can be much more than a cost, a constraint, or a charitable deed – it can indeed be a potent source of innovation and competitive advantage. The above framework illustrates from the authors’ perspective how strategic CSR can positively or negatively have an effect on organisational performance.

5. Discussion and Managerial Implications

Strategic CSR when assimilated well into the organisation’s overall business approach contributes a great deal to the reputation and image building of the organisation. There is a lot of empirical evidence that have established a positive relationship between firm public perception/reputation and its financial and equity market performance. For example, Chung et. al. (1999) focused on how a company’s reputation influences the value of its stock in the stock market. However, for CSR to succeed management of organisations must play a major role both in the promotion and implementation of strategic CSR activities. CSR must be managed from a top-down perspective, implying that CSR must be actively managed from top executives. This is in accordance to Fairhurst’s (2007) claim that leaders as agents of transformation have the ability to construct the environment to which they and their subordinates must respond to organisational responsibilities. Accordingly, top management must embrace a strong stand on social responsibility and develop a policy statement that entails commitment to the strategic CSR stratagem.

Strategic CSR can unearth hidden previously unknown opportunities in the community that the organisation did not know. Given that businesses undertake strategic CSR to create reciprocal value for the community and the firm, Firms can easily identify new innovations and swiftly take advantage of these new opportunities to further their organisational goals.

6. Conclusion

Some viable conclusions can be drawn from this study. CSR is not only about providing a safe workplace or meeting environmental regulations. Neither is CSR all about altruism – managers are not doing more than what the law requires of them because they are saints but because it is in the long-term best interest of their corporations’ sustentation. Strategic CSR as a concept refers to the corporate behaviour that is over and above legal requirements and it is voluntarily adopted to achieve sustainable development. Corporations have realized that they need to integrate the economic, social, and environmental impacts of their operations and form an appropriate corporate policy which, in the long-term, benefits all stakeholders.

CSR is increasingly becoming expected in business stratagem and can be rewarding for both societal stakeholders and the firm. Ethical and altruistic CSR are the mandatory minimal level of social responsibility an enterprise owes its constituencies but given that the ultimate responsibility of a corporation is to create value for its stakeholders, strategic CSR which financially benefits the business through serving society in extra economic ways, is justifiable and from society’s perspective, should be integrated into business activities to create additional value whilst bolstering up the overall performance and productivity of the firm.

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.