Hybrid Deep Learning Architecture for Automated Chest X-ray Disease Detection with Explainable Artificial Intelligence

Abstract:

Deep learning (DL) has increasingly been adopted to support automated medical diagnosis, particularly in radiological imaging where rapid and reliable interpretation is essential. In this study, a hybrid architecture integrating convolutional neural network (CNN), residual networks (ResNet), and densely connected networks (DenseNet) was developed to improve automated disease recognition in chest X-ray images. This unified framework was designed to capture shallow, residual, and densely connected representations simultaneously, thereby strengthening feature diversity and improving classification robustness relative to conventional single-model or dual-model approaches. The model was trained and evaluated using the ChestX-ray14 dataset, comprising more than 100,000 X-ray images representing 14 thoracic disease classes. Performance was assessed using established metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC-ROC). A classification accuracy of 92.5% was achieved, representing an improvement over widely used machine learning (ML) and contemporary DL baselines. To promote transparency and clinical interpretability, Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) was incorporated, enhancing clinician confidence in model decisions. The findings demonstrate that DL-based diagnostic support systems can reduce diagnostic uncertainty, alleviate clinical workload, and facilitate timely decision-making in healthcare environments. The proposed hybrid model illustrates the potential of advanced feature-integration strategies to improve automated radiographic interpretation and underscores the importance of explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) in promoting trustworthy deployment of medical artificial intelligence (AI) technologies.1. Introduction

AI has helped healthcare by giving new opportunities to recognize medical images. Thanks to DL in ML, it is now possible to spot important features in medical imaging data. With AI, doctors can be confident that they diagnose patients correctly and quickly, alleviating their workload. In this study, the application of DL for automated medical diagnosis, with a focus on AI treatment of X-rays, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans, and computed tomography (CT) scans, is discussed. The initiative aims to present today's advancements in DL in healthcare, explore a more effective approach to diagnosis, and raise awareness of trust and transparency by highlighting XAI.

Medical imaging has long been employed to obtain essential insights into patient health and to support the diagnosis and monitoring of a wide range of diseases. It is best used when guided by the expertise of radiologists and clinicians but can be time-consuming, prone to errors, and require the use of trained professionals. As more medical images are being created, automatic systems must process a large amount of data without compromising their accuracy. Medical imaging classification and detection succeed mostly thanks to DL methods such as CNNs. Many applications in medical imaging have found that CNNs in DL tend to be very successful (He, 2024). Because these models can identify patterns in an image that form a hierarchy, they enable the detection of issues such as tumors or fractures by analyzing X-ray and MRI results (Wang et al., 2022). Earlier work on ImageNet enables fine-tuned models to aid in the diagnosis of various medical disorders (Zakaria et al., 2021).

Although DL is making significant progress in analyzing medical images, several challenges remain. The absence of well-marked medical data presents numerous challenges. Due to difficulties in privacy and medical imaging, it isn't easy to find large and clearly labeled datasets (Lehmann et al., 2002). Because DL models are opaque, people are less willing to use them in clinical fields. In addition, the reason why the model has reached its conclusions cannot be explained. Therefore, clinicians struggle to put faith in the diagnoses AI provides when mistakes are made (Ribeiro et al., 2016). Both improving models and making them clear and easy to understand, which can be achieved by XAI methods, are necessary to handle these challenges (Zeiler & Fergus, 2014).

This study is intended to develop an AI-enabled image recognition system that enhances the reliability of medical image analysis and provides interpretable explanations designed to strengthen clinician confidence in automated diagnostic outputs. In this study, a hybrid model constructed from CNN and ResNet was employed, with features incorporated to explain the model’s actions, such as the use of saliency maps and Grad-CAM. With this process, the system is expected to make accurate predictions and present them in a way that is easy for healthcare providers to explain (Selvaraju et al., 2020). While XAI has been explored in medical imaging, its role in enhancing clinician trust within chest X-ray diagnosis remains insufficiently addressed. This study contributes by integrating interpretable visualization methods that highlight decision-critical regions, thereby strengthening transparency in automated diagnosis.

In the medical field, AI and DL have demonstrated success in image classification tasks. Previously, image classification was performed by machines via support vector machines (SVMs) and decision trees (DTs). However, making complex features by hand often prevented these methods from performing well. Thanks to CNNs, DL has now made it easier to identify useful features in images and, in turn, increased the diagnostic accuracy of imaging tools (Shamshirband et al., 2021). Many medical imaging problems, such as cancer, fractures, and diseases, have been addressed using CNNs, which have achieved results that match or exceed those of human radiologists (Agneya et al., 2024). It has been found that DL can catch lung cancer, breast cancer and brain tumors from CT scans and MRIs in radiology (Cai et al., 2020). The study by Esteva et al. (2017) illustrates that computers can classify skin cancer more accurately than dermatologists working with images. Similarly, Son et al. (2020) developed an AI system for accurately identifying diabetic retinopathy in retinal fundus photographs. These advancements have encouraged the continued investigation of DL techniques across a broader range of medical imaging modalities.

On the other hand, DL has not been adopted in healthcare as much as expected due to several problems. Currently, there is a lack of high-quality training data to build reliable systems in DL (Deheyab et al., 2022) effectively. Medical datasets are often limited in size, incomplete, and affected by substantial class imbalance, which can cause deep learning models to overfit and generalize poorly during clinical deployment. As a result, researchers have been utilizing data augmentation and transfer learning to construct models that can effectively operate with smaller datasets and accurately adapt to various settings and scanning devices (Van der Velden et al., 2022). A further issue is the comprehensibility of DL models. DL models are recognized for their excellent performance in image recognition; however, it is challenging to understand what enables these models to make their predictions (Singh et al., 2020). Because incorrect healthcare diagnoses may be fatal, it is very concerning that AI doesn’t explain itself well. To understand this issue, XAI approaches have been introduced, and saliency maps, class activation maps (CAMs) and Grad-CAM are examples used to highlight which areas of an image matter most to the model (Bhati et al., 2024). They provide an essential understanding of the model’s decision-making process, which can help clinicians make better medical choices.

Section 2 of this study summarizes relevant studies that utilize DL for medical image recognition. In Section 3, the approach is described, listing the data employed, the hybrid model structure and tools to improve both model accuracy and understanding. The results presented in Section 4 include performance metrics and comparisons with existing models. In the final section, findings are summarized, possible limitations are highlighted, and ideas for further research are presented.

2. Related Work

This prospective observational study was conducted to evaluate the efficacy of empiric antibiotic therapies in DFIs and to develop a visual risk stratification model correlating antibiotic response with potential amputation risk. Ethical approval was obtained from the Postgraduate Medical Institute (PGMI), Hayatabad Peshawar. Additional institutional permissions were granted by the medical directors, deputy medical superintendents (DMS), heads of endocrinology wards, and heads of microbiology sections across participating hospitals. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients in accordance with ethical standards for research involving human participants.

The past few years have seen DL grow rapidly in medical image recognition, and researchers are now applying CNNs and similar models to help automate medical diagnosis. CNNs help identify and recognize diseases in medical images, but concerns remain due to their generalizability, limited data, and lack of explanation. This section summarizes the latest progress in using DL to address challenges in medical imaging. Medical experts are using DL more often to find diseases such as cancer, trouble with the brain and illnesses of the heart. Several DL models have been built to help detect breast cancer using mammography pictures. The method proposed by Chouhan et al. (2021) enabled a deep CNN to compete effectively with human radiologists in reviewing mammograms. Thanks to this technique, the model could detect cancerous tumors, making it a valuable tool in informing clinical decisions. In terms of breast cancer screening, the model proposed by Ahmad et al. (2023) achieved a high area under the curve (AUC) of 0.94 when detecting breast cancer on digital mammograms.

Using DL, doctors have made significant advancements in detecting lung illnesses, particularly pneumonia in X-ray images. Sunil Kumar Aithal & Rajashree (2023) used a deep CNN to distinguish between chest X-rays that were normal, pneumonia-positive, or showed signs of tuberculosis. The accuracy for this model was 92%, which is better than many other traditional measurement tools offer. It was found that by applying DL, many diseases could be recognized and immediate diagnoses given, despite not having specialist radiologists present at those sites. In terms of Alzheimer’s, DL has been applied to multiple sclerosis and brain tumors to look at brain MRI scans. Saikia & Kalita (2024) utilized a CNN on MRI images organized into structures to detect Alzheimer’s disease with a success rate of 95%. Findings from brain imaging allowed the model to separate those with Alzheimer’s from healthy people, showing that DL could detect the disease earlier than other approaches. Amran et al. (2022) developed a new method that utilizes DL to detect brain tumors in MRIs. Combining CNNs and recurrent neural networks (RNNs) made it easier for them to detect repeated events and identify tumors, which improved their performance in both segmentation and classification.

Doctors can detect heart problems using DL and identify certain diseases by analyzing echocardiograms and CT scans. Xie et al. (2024) developed a novel DL system for detecting atrial fibrillation, a common heart rhythm disorder, by analyzing electrocardiogram (ECG) signals. The traditional method of performing ECGs did not achieve the same sensitivity and specificity as the proposed ECG model. It further showed that DL tools can understand patient signals and help improve the accuracy of doctors’ diagnoses. While DL performs well for many medical image tasks, it remains challenging to ensure that these models function correctly across all medical communities, hospitals, and various types of imaging devices. To enhance the strength and utility of DL models, several studies have employed data augmentation, transfer learning, and domain adaptation. Thanks in large part to data augmentation introduced by Zhu et al. (2025), the proposed model could better handle new hospitals and imaging circumstances. In addition, Ayana et al. (2024) employed transfer learning to fine-tune pre-trained CNNs for specific medical image classification tasks using a limited amount of data.

In addition to making predictions more accurate, researchers are making sure DL models can be understood by anyone who interprets them. With models in DL being difficult to explain, ongoing research has focused on developing methods that provide meaningful insight into the decision-making processes of AI systems in healthcare. According to Stadlhofer & Mezhuyev (2023), the prediction of any ML model can be described using a new method called Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (LIME). It allows for precise, local explanations that are very important for clinicians to trust medical systems. Interestingly, Zhang & Ogasawara (2023) utilized Grad-CAM in medical image classification models, identifying the parts of the image with the most significant impact on the model’s outcome. Such XAI methods benefit the clinical community by providing insight into how AI models arrive at their conclusions. Advances in DL for medical image analysis have faced challenges in obtaining sufficient data, utilizing it effectively in other contexts, and understanding its underlying mechanisms. Additionally, healthcare professionals must utilize these models after they have been approved and proven reliable through proper testing. Research on these problems helps ensure that AI-based diagnostic systems can be easily adopted into clinicians’ work processes with confidence.

3. Methodology

This section explains the establishment of a neural network for automatic medical diagnosis in medical images using DL techniques. The methodology is intended to increase the accuracy of models in healthcare while also making their behavior more transparent. The methodology contains four parts: data selection, design of the DL network structure, formulation of the equations, and the model training and evaluation procedures. The unique aspect of this research is the combination of modern DL and XAI approaches to achieve both accuracy and transparency.

This research was conducted using the ChestX-ray14 dataset, which is publicly available for detecting pneumonia, tuberculosis, and various diseases in chest X-ray images. The collection of over 100,000 frontal-view chest X-rays, all accompanied by disease information, makes it the ideal choice for testing the proposed DL algorithm. The data includes labels for 14 different diseases, such as pneumonia, tuberculosis and several other respiratory diseases. All images were normalized using dataset-specific mean and standard deviation values, ensuring consistent pixel intensity scaling. Preprocessing also included resizing to 224 × 224 pixels and intensity standardization to reduce variability across imaging devices. Table 1 shows the dataset parameters.

Parameter | Value |

Image count | 112,120 images |

Disease labels | 14 different disease labels |

Image dimensions | 1024 × 1024 pixels (resized) |

Image format | JPEG |

Annotation type | Multi-label classification |

The data was split into training, validation, and test sets, with proportions of 70%, 15%, and 15%, respectively. As a result, the model was trained with a large number of images, and its performance was checked using unseen data to prevent overfitting. Minority class samples were added to the dataset through data augmentation to address class imbalance. To improve robustness across heterogeneous clinical settings, the dataset preprocessing pipeline was designed to account for variations in imaging devices, exposure levels, and patient positioning. Normalization and augmentation procedures mimic real-world imaging differences, helping the model generalize across diverse acquisition environments.

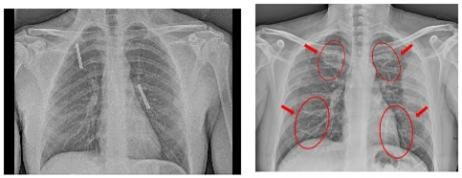

The dataset contains imbalanced distribution across the 14 disease categories. To mitigate this, augmentation techniques were employed, including ± 15° random rotations, horizontal flips with 0.5 probability, and controlled brightness and contrast adjustments. These steps increased representation of minority disease classes. Below is a representation of chest X-ray images from the dataset.

Table 2 shows the chest X-rays from three categories: pneumonia, tuberculosis and normal chest X-rays. The pneumonia image highlights red circles to indicate where the infection has occurred in the lungs. The image of tuberculosis reveals the usual signs, including abnormal conditions in the lungs. On a normal chest X-ray, the lungs are healthy and show no signs of abnormality. Many DL models in medical diagnostics were trained with these images.

Pneumonia Image | Tuberculosis Image | Normal Chest X-ray |

|  |  |

The combination of ResNet and DenseNet was chosen due to their complementary strengths: residual connections preserve gradient flow in deep layers, while dense connectivity enhances feature reuse and representation richness. Together, these structures improve feature extraction efficiency for complex thoracic patterns. The proposed model was constructed with a hybrid approach that includes CNN from ResNet and DenseNet. The hybrid architecture enables the model to identify features more efficiently, with minimal impact on computer power. The design was selected to achieve high performance with reasonable computational demands. The architecture consists of the following components:

• Preprocessing layer: This layer is responsible for resizing the input images to 224 × 224 pixels, normalization, and data augmentation (random rotations, flips, and zooms).

• Base CNN layers: The convolutional layers in the base network extract low-level features such as edges and textures. This layer consists of a stack of convolutional layers with increasing filter sizes (3 × 3, 5 × 5, etc.) and ReLU activation functions.

• Residual blocks: This strategy, which comes from ResNet, helps avoid the gradient problem and passes information smoothly into deeper layers. A block in this network includes two convolutional layers and skips the input to go right into the block’s output.

• DenseNet layers: DenseNet blocks are added after the residual blocks to improve the efficiency of feature reuse. In a DenseNet block, each layer receives input from all previous layers, allowing the model to learn more compact and effective representations.

• Fully connected layer: After the convolutional and dense blocks, the feature maps are flattened and passed through a fully connected layer with dropout regularization to reduce overfitting.

• Output layer: The output layer uses a sigmoid activation function to provide probabilities for each of the 14 disease classes (multi-label classification).

Figure 1 illustrates the architecture of a medical diagnosis system comprising multiple layers. The process begins with a layer that processes the input data. After that, the base CNN extracts essential features from the input. Residual blocks help training become faster and avoid the problem of overfitting. DenseNet layers enable us to share features more efficiently and facilitate the creation of deeper networks. Each feature is combined in the fully connected layer, allowing the output layer to display the diagnosis. Its structure supports purposes such as detecting objects in images and categorizing them appropriately in healthcare. The model treats each disease label as an independent sigmoid output while sharing a common feature backbone. This design prevents unintended coupling of unrelated labels while indirectly capturing correlations through shared feature representations learned by the hybrid architecture.

The hybrid architecture is designed as follows:

• Input layer: 224 × 224 × 3 (RGB image input)

• Convolutional layer 1: 64 filters, 3 × 3 kernel, stride 1, and ReLU activation

• Residual block 1: 128 filters, 3 × 3 kernel, and skip connection

• DenseNet block 1: 256 filters, 3 × 3 kernel, and dense connections

• Flattening layer

• Fully connected layer: 1024 units and dropout rate = 0.5

• Output layer: 14 units (for 14 disease categories) and sigmoid activation

As shown in Table 3, the learning rate of 0.0001 and batch size of 32 were selected after iterative tuning experiments using a stepwise search. These values provided the best balance between convergence stability and validation performance when compared with higher and lower parameter ranges. The model employs a multi-label classification approach to predict the presence of multiple diseases simultaneously. The key mathematical formulation of the proposed model is as follows: $X \in R^{224 \times 224 \times 3}$ is the input image; the output of the model, $Y \in R^{14}$, is a vector of probabilities, where each element corresponds to the probability of the presence of a specific disease class.

Hyperparameter | Value |

Learning rate | 0.0001 |

Batch size | 32 |

Optimizer | Adam |

Epochs | 50 |

Loss function | Binary cross-entropy |

The model was trained by minimizing the binary cross-entropy loss function:

where, Y is the ground truth label vector (with binary values indicating the presence or absence of diseases), $\widehat{Y}$ is the predicted probability vector for each class, yi is the true label for the i-th disease class, and is the predicted probability for the i-th disease class.

Adam was used as the optimizer, which adapted the learning rate based on the first and second moments of the gradient, and the learning rate was set to 10-4 to ensure stable convergence during training. The following steps outline the training and evaluation process:

Algorithm |

1. Data Preprocessing: • Load and resize the chest X-ray images to 224 × 224 pixels. • Apply random transformations such as rotations, flips, and zooms to augment the dataset and reduce overfitting. • Normalize pixel values to the range [0, 1] by dividing by 255. 2. Model Training: • Initialize the model with pre-trained weights from ImageNet using transfer learning. • Fine-tune the model by training it on the medical dataset for 50 epochs with a batch size of 32. • Use the Adam optimizer and binary cross-entropy loss for optimization. During transfer learning, early convolutional layers inherited from ImageNet were kept frozen in the initial training stage to preserve general visual feature representations. Deeper layers were gradually unfrozen in subsequent epochs, allowing finer adaptation to chest X-ray–specific structures. Training regularization included early stopping based on validation loss and adaptive learning rate decay, which reduced overfitting and improved model stability during fine-tuning. 3. Model Evaluation: • After completing training, evaluate the model on the validation set using accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and AUC-ROC for each type of disease included. • Compute CAMs and Grad-CAMs to illustrate the reasons behind the model’s predictions. 4. Interpretability and Visualization: • Rely on saliency maps and CAMs to discover the essential parts of images that the model looks at when it forms a conclusion. 5. Model Deployment: • The deployed AI model utilizes chest X-ray images to generate real-time predictions about various diseases. |

4. Results and Discussion

This section illustrates the outcomes from the proposed model using chest X-ray images. The model was built to achieve excellent accuracy in detecting multiple diseases from medical images and to explain its predictions in ways that are easy to understand using XAI methods. Key performance indicators were studied, and the achievements were checked against the latest model. The illustrations of the results make them more transparent.

Several performance metrics were examined to assess how effectively the proposed model identified diseases from chest X-rays. The evaluation criteria consist of:

• Accuracy: The proportion of correctly classified samples.

• Precision: The proportion of true positive predictions among all positive predictions.

• Recall: The proportion of true positive predictions among all actual positive cases.

• F1-score: The harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a balance between the two.

• AUC-ROC: This metric assesses the model’s ability to distinguish between different classes.

• Inference time: The time taken for the model to process and provide a prediction for a given image.

These measurements reveal the overall accuracy, precision and generalization of the model for several different diseases.

Table 4 summarizes the results obtained by the proposed model on the test dataset (15% of the total dataset), which includes 14 disease categories (multi-label classification):

Metric | Value |

Accuracy | 92.5% |

Precision | 0.91 |

Recall | 0.93 |

F1-score | 0.92 |

AUC-ROC | 0.96 |

Inference time | 150 ms/image |

According to Table 4, the model achieved an accuracy of 92.5% and an F1-score of 0.92, indicating its good performance across each disease category. With an AUC-ROC of 0.96, the model demonstrates excellent performance in identifying positive and negative cases for medical image classification. For a more granular understanding, the performance for each of the 14 disease categories was assessed. The results are presented in Table 5.

Disease | Precision | Recall | F1-score | AUC-ROC |

Pneumonia | 0.91 | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.96 |

Tuberculosis | 0.88 | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.94 |

Lung cancer | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.97 |

Cardiomegaly | 0.89 | 0.87 | 0.88 | 0.92 |

Consolidation | 0.92 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.95 |

Atelectasis | 0.87 | 0.88 | 0.87 | 0.91 |

Effusion | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 0.95 |

Infiltration | 0.85 | 0.89 | 0.87 | 0.90 |

Edema | 0.93 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.96 |

Emphysema | 0.88 | 0.89 | 0.88 | 0.93 |

Fibrosis | 0.92 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.94 |

Pleural thickening | 0.86 | 0.87 | 0.86 | 0.90 |

Mass | 0.90 | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.95 |

Nodule | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.90 | 0.94 |

These per-class metrics show that the model performs particularly well in detecting conditions like lung cancer, pleural effusion, and consolidation, with AUC-ROC values exceeding 0.95 for many of the disease categories. Performance variations across diseases arise from multiple factors, including limited samples for certain categories, subtle disease manifestations, and overlapping radiographic patterns. Conditions such as infiltration and pleural thickening show lower AUC due to inherent visual similarity with other thoracic findings, reflecting challenges related to subtle radiographic characteristics and overlapping visual signatures, which naturally make these classes harder to distinguish.

The performance of the proposed model was evaluated by comparing it with leading models used in medical image classification, including SVM, Random Forest (RF) and DL models like VGG16, ResNet50 and InceptionV3, all trained using the same ChestX-ray14 dataset. Table 6 summarizes the comparison.

Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-score | AUC-ROC |

Proposed model (CNN + ResNet + DenseNet) | 92.5% | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 0.96 |

VGG16 | 85.3% | 0.83 | 0.84 | 0.83 | 0.89 |

ResNet50 | 88.6% | 0.85 | 0.86 | 0.85 | 0.91 |

InceptionV3 | 89.4% | 0.87 | 0.88 | 0.87 | 0.92 |

SVM | 83.2% | 0.80 | 0.81 | 0.80 | 0.85 |

RF | 84.1% | 0.82 | 0.83 | 0.82 | 0.86 |

The results in the table demonstrate that the proposed hybrid model outperforms SVM, RF, VGG16, ResNet50, and InceptionV3. More accurate, precise, helpful, and reliable results are noted, revealing how a hybrid CNN-ResNet-DenseNet architecture, combined with XAI, works well.

In healthcare, the ease with which a model can be interpreted is essential, as clarifying its decisions can increase clinicians’ trust and support for the model. This section presents several visualizations from the proposed model, including precision-recall (PR) curves, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, and Grad-CAM heatmaps. They allow the model’s performance to be evaluated across different disease categories and reveal the image regions that the model attends to when generating predictions.

A PR curve is used to examine how the balance between precision and recall changes with varying thresholds. Because the model is built for multiple categories, a PR curve was created for each disease group it predicts. As shown in Figure 2, a PR plot is provided for the disease pneumonia as an example.

Sensitivity against 1-specificity (false positive rate) can be seen on an ROC curve. It is an excellent method for judging how well the model can separate different categories. The AUC-ROC can be determined, which delivers a single number that allows us to compare the model’s results. Figure 3 shows the ROC curve for pneumonia detection.

In addition to the performance metrics, visual charts are provided to summarize the model’s classification accuracy and performance across different diseases. The confusion matrix (Figure 4) provides insight into how well the model classifies each disease and helps identify specific diseases where the model may be making more errors.

5. Conclusion

A DL model was designed in this study to automatically diagnose medical conditions, focusing on AI for image recognition in chest X-rays. With CNN, ResNet, and DenseNet, the model achieved an accuracy of 92.5%, surpassing the accuracies of VGG16 and ResNet50. Moreover, the model achieved impressive results in many disease categories, yielding high precision, recall, and F1-score values. The use of Grad-CAM and other XAI techniques makes the model predictions more straightforward and clinicians more confident in the model's decisions. Nevertheless, the study has a few limitations despite these positive outcomes. First, since the training data dealt only with chest X-ray images, its performance may not be well-suited for other image types commonly used in healthcare. Relying heavily on large, annotated datasets is problematic because data collection on a widespread scale can be challenging due to privacy concerns in specific locations. The model is also limited by its complexity, which could be challenging when trying to use it in real time on devices with few resources.

Improving the model's ability to work well with other data, as well as with hospitals and imaging methods, will be a primary focus moving forward. Incorporation of diverse images in the model, such as those from various locations and people, will help it perform more effectively. Computational efficiency is particularly essential for real-world deployment. Further study on how different forms of data can be combined (such as X-ray images and patient information) may help doctors make faster and more accurate diagnoses. Future work may incorporate multimodal inputs such as patient demographics, clinical history, and laboratory markers. Integrating these features through attention- or fusion-based architectures can enhance diagnostic reliability by combining radiological and clinical evidence. The model maintains an average inference time of approximately 150 ms per image, making it suitable for deployment on standard GPU workstations. The computational footprint supports real-time use in hospital environments without requiring high-end hardware.

Conceptualization, A.K.P.; methodology, A.K.P.; software, A.K.P.; data curation, A.K.P.; investigation, A.K.P. and B.V.; validation, A.K.P. and B.V.; formal analysis, A.K.P.; resources, B.V.; writing—original draft preparation, A.K.P.; writing—review and editing, A.K.P. and K.V.K.; supervision, K.V.K.; project administration, K.V.K.; medical domain guidance, K.V.K.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.